Just a few weeks in the past, we supplied an introduction to the duty of naming and finding objects in pictures.

Crucially, we confined ourselves to detecting a single object in a picture. Studying that article, you may need thought “can’t we simply prolong this strategy to a number of objects?” The brief reply is, not in a simple method. We’ll see an extended reply shortly.

On this put up, we need to element one viable strategy, explaining (and coding) the steps concerned. We received’t, nonetheless, find yourself with a production-ready mannequin. So should you learn on, you received’t have a mannequin you possibly can export and put in your smartphone, to be used within the wild. It is best to, nonetheless, have discovered a bit about how this – object detection – is even doable. In spite of everything, it’d seem like magic!

The code under is closely primarily based on quick.ai’s implementation of SSD. Whereas this isn’t the primary time we’re “porting” quick.ai fashions, on this case we discovered variations in execution fashions between PyTorch and TensorFlow to be particularly putting, and we are going to briefly contact on this in our dialogue.

So why is object detection exhausting?

As we noticed, we will classify and detect a single object as follows. We make use of a robust characteristic extractor, reminiscent of Resnet 50, add a number of conv layers for specialization, after which, concatenate two outputs: one which signifies class, and one which has 4 coordinates specifying a bounding field.

Now, to detect a number of objects, can’t we simply have a number of class outputs, and several other bounding packing containers?

Sadly we will’t. Assume there are two cute cats within the picture, and we have now simply two bounding field detectors.

How does every of them know which cat to detect? What occurs in follow is that each of them attempt to designate each cats, so we find yourself with two bounding packing containers within the center – the place there’s no cat. It’s a bit like averaging a bimodal distribution.

What might be accomplished? General, there are three approaches to object detection, differing in efficiency in each frequent senses of the phrase: execution time and precision.

In all probability the primary choice you’d consider (should you haven’t been uncovered to the subject earlier than) is operating the algorithm over the picture piece by piece. That is referred to as the sliding home windows strategy, and regardless that in a naive implementation, it might require extreme time, it may be run successfully if making use of absolutely convolutional fashions (cf. Overfeat (Sermanet et al. 2013)).

Presently the most effective precision is gained from area proposal approaches (R-CNN(Girshick et al. 2013), Quick R-CNN(Girshick 2015), Sooner R-CNN(Ren et al. 2015)). These function in two steps. A primary step factors out areas of curiosity in a picture. Then, a convnet classifies and localizes the objects in every area.

In step one, initially non-deep-learning algorithms have been used. With Sooner R-CNN although, a convnet takes care of area proposal as properly, such that the tactic now could be “absolutely deep studying.”

Final however not least, there’s the category of single shot detectors, like YOLO(Redmon et al. 2015)(Redmon and Farhadi 2016)(Redmon and Farhadi 2018)and SSD(Liu et al. 2015). Simply as Overfeat, these do a single go solely, however they add a further characteristic that enhances precision: anchor packing containers.

Anchor packing containers are prototypical object shapes, organized systematically over the picture. Within the easiest case, these can simply be rectangles (squares) unfold out systematically in a grid. A easy grid already solves the fundamental downside we began with, above: How does every detector know which object to detect? In a single-shot strategy like SSD, every detector is mapped to – accountable for – a particular anchor field. We’ll see how this may be achieved under.

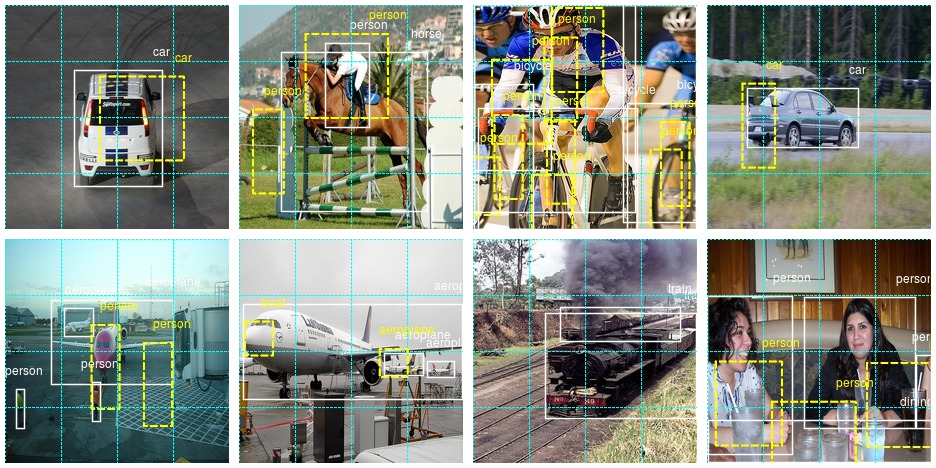

What if we have now a number of objects in a grid cell? We will assign multiple anchor field to every cell. Anchor packing containers are created with completely different side ratios, to supply an excellent match to entities of various proportions, reminiscent of individuals or timber on the one hand, and bicycles or balconies on the opposite. You may see these completely different anchor packing containers within the above determine, in illustrations b and c.

Now, what if an object spans a number of grid cells, and even the entire picture? It received’t have adequate overlap with any of the packing containers to permit for profitable detection. For that motive, SSD places detectors at a number of phases within the mannequin – a set of detectors after every successive step of downscaling. We see 8×8 and 4×4 grids within the determine above.

On this put up, we present the way to code a very fundamental single-shot strategy, impressed by SSD however not going to full lengths. We’ll have a fundamental 16×16 grid of uniform anchors, all utilized on the identical decision. In the long run, we point out the way to prolong this to completely different side ratios and resolutions, specializing in the mannequin structure.

A fundamental single-shot detector

We’re utilizing the identical dataset as in Naming and finding objects in pictures – Pascal VOC, the 2007 version – and we begin out with the identical preprocessing steps, up and till we have now an object imageinfo that comprises, in each row, details about a single object in a picture.

Additional preprocessing

To have the ability to detect a number of objects, we have to combination all info on a single picture right into a single row.

imageinfo4ssd <- imageinfo %>%

choose(category_id,

file_name,

title,

x_left,

y_top,

x_right,

y_bottom,

ends_with("scaled"))

imageinfo4ssd <- imageinfo4ssd %>%

group_by(file_name) %>%

summarise(

classes = toString(category_id),

title = toString(title),

xl = toString(x_left_scaled),

yt = toString(y_top_scaled),

xr = toString(x_right_scaled),

yb = toString(y_bottom_scaled),

xl_orig = toString(x_left),

yt_orig = toString(y_top),

xr_orig = toString(x_right),

yb_orig = toString(y_bottom),

cnt = n()

)Let’s test we acquired this proper.

instance <- imageinfo4ssd[5, ]

img <- image_read(file.path(img_dir, instance$file_name))

title <- (instance$title %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

x_left <- (instance$xl_orig %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

x_right <- (instance$xr_orig %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

y_top <- (instance$yt_orig %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

y_bottom <- (instance$yb_orig %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

img <- image_draw(img)

for (i in 1:instance$cnt) {

rect(x_left[i],

y_bottom[i],

x_right[i],

y_top[i],

border = "white",

lwd = 2)

textual content(

x = as.integer(x_right[i]),

y = as.integer(y_top[i]),

labels = title[i],

offset = 1,

pos = 2,

cex = 1,

col = "white"

)

}

dev.off()

print(img)

Now we assemble the anchor packing containers.

Anchors

Like we stated above, right here we could have one anchor field per cell. Thus, grid cells and anchor packing containers, in our case, are the identical factor, and we’ll name them by each names, interchangingly, relying on the context.

Simply remember the fact that in additional complicated fashions, these will most likely be completely different entities.

Our grid might be of measurement 4×4. We’ll want the cells’ coordinates, and we’ll begin with a heart x – heart y – top – width illustration.

Right here, first, are the middle coordinates.

We will plot them.

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = anchor_xs, y = anchor_ys), aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0,1), ylim = c(0,1)) +

theme(side.ratio = 1)

The middle coordinates are supplemented by top and width:

Combining facilities, heights and widths provides us the primary illustration.

anchors <- cbind(anchor_centers, anchor_height_width)

anchors [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 0.125 0.125 0.25 0.25

[2,] 0.125 0.375 0.25 0.25

[3,] 0.125 0.625 0.25 0.25

[4,] 0.125 0.875 0.25 0.25

[5,] 0.375 0.125 0.25 0.25

[6,] 0.375 0.375 0.25 0.25

[7,] 0.375 0.625 0.25 0.25

[8,] 0.375 0.875 0.25 0.25

[9,] 0.625 0.125 0.25 0.25

[10,] 0.625 0.375 0.25 0.25

[11,] 0.625 0.625 0.25 0.25

[12,] 0.625 0.875 0.25 0.25

[13,] 0.875 0.125 0.25 0.25

[14,] 0.875 0.375 0.25 0.25

[15,] 0.875 0.625 0.25 0.25

[16,] 0.875 0.875 0.25 0.25In subsequent manipulations, we are going to typically we’d like a special illustration: the corners (top-left, top-right, bottom-right, bottom-left) of the grid cells.

hw2corners <- operate(facilities, height_width) {

cbind(facilities - height_width / 2, facilities + height_width / 2) %>% unname()

}

# cells are indicated by (xl, yt, xr, yb)

# successive rows first go down within the picture, then to the correct

anchor_corners <- hw2corners(anchor_centers, anchor_height_width)

anchor_corners [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 0.00 0.00 0.25 0.25

[2,] 0.00 0.25 0.25 0.50

[3,] 0.00 0.50 0.25 0.75

[4,] 0.00 0.75 0.25 1.00

[5,] 0.25 0.00 0.50 0.25

[6,] 0.25 0.25 0.50 0.50

[7,] 0.25 0.50 0.50 0.75

[8,] 0.25 0.75 0.50 1.00

[9,] 0.50 0.00 0.75 0.25

[10,] 0.50 0.25 0.75 0.50

[11,] 0.50 0.50 0.75 0.75

[12,] 0.50 0.75 0.75 1.00

[13,] 0.75 0.00 1.00 0.25

[14,] 0.75 0.25 1.00 0.50

[15,] 0.75 0.50 1.00 0.75

[16,] 0.75 0.75 1.00 1.00Let’s take our pattern picture once more and plot it, this time together with the grid cells.

Observe that we show the scaled picture now – the way in which the community goes to see it.

instance <- imageinfo4ssd[5, ]

title <- (instance$title %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

x_left <- (instance$xl %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

x_right <- (instance$xr %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

y_top <- (instance$yt %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

y_bottom <- (instance$yb %>% str_split(sample = ", "))[[1]]

img <- image_read(file.path(img_dir, instance$file_name))

img <- image_resize(img, geometry = "224x224!")

img <- image_draw(img)

for (i in 1:instance$cnt) {

rect(x_left[i],

y_bottom[i],

x_right[i],

y_top[i],

border = "white",

lwd = 2)

textual content(

x = as.integer(x_right[i]),

y = as.integer(y_top[i]),

labels = title[i],

offset = 0,

pos = 2,

cex = 1,

col = "white"

)

}

for (i in 1:nrow(anchor_corners)) {

rect(

anchor_corners[i, 1] * 224,

anchor_corners[i, 4] * 224,

anchor_corners[i, 3] * 224,

anchor_corners[i, 2] * 224,

border = "cyan",

lwd = 1,

lty = 3

)

}

dev.off()

print(img)

Now it’s time to deal with the presumably biggest thriller while you’re new to object detection: How do you really assemble the bottom fact enter to the community?

That’s the so-called “matching downside.”

Matching downside

To coach the community, we have to assign the bottom fact packing containers to the grid cells/anchor packing containers. We do that primarily based on overlap between bounding packing containers on the one hand, and anchor packing containers on the opposite.

Overlap is computed utilizing Intersection over Union (IoU, =Jaccard Index), as standard.

Assume we’ve already computed the Jaccard index for all floor fact field – grid cell combos. We then use the next algorithm:

-

For every floor fact object, discover the grid cell it maximally overlaps with.

-

For every grid cell, discover the article it overlaps with most.

-

In each circumstances, determine the entity of biggest overlap in addition to the quantity of overlap.

-

When criterium (1) applies, it overrides criterium (2).

-

When criterium (1) applies, set the quantity overlap to a continuing, excessive worth: 1.99.

-

Return the mixed outcome, that’s, for every grid cell, the article and quantity of greatest (as per the above standards) overlap.

Right here’s the implementation.

# overlaps form is: variety of floor fact objects * variety of grid cells

map_to_ground_truth <- operate(overlaps) {

# for every floor fact object, discover maximally overlapping cell (crit. 1)

# measure of overlap, form: variety of floor fact objects

prior_overlap <- apply(overlaps, 1, max)

# which cell is that this, for every object

prior_idx <- apply(overlaps, 1, which.max)

# for every grid cell, what object does it overlap with most (crit. 2)

# measure of overlap, form: variety of grid cells

gt_overlap <- apply(overlaps, 2, max)

# which object is that this, for every cell

gt_idx <- apply(overlaps, 2, which.max)

# set all positively overlapping cells to respective object (crit. 1)

gt_overlap[prior_idx] <- 1.99

# now nonetheless set all others to greatest match by crit. 2

# really it is different method spherical, we begin from (2) and overwrite with (1)

for (i in 1:size(prior_idx)) {

# iterate over all cells "completely assigned"

p <- prior_idx[i] # get respective grid cell

gt_idx[p] <- i # assign this cell the article quantity

}

# return: for every grid cell, object it overlaps with most + measure of overlap

checklist(gt_overlap, gt_idx)

}Now right here’s the IoU calculation we’d like for that. We will’t simply use the IoU operate from the earlier put up as a result of this time, we need to compute overlaps with all grid cells concurrently.

It’s best to do that utilizing tensors, so we quickly convert the R matrices to tensors:

# compute IOU

jaccard <- operate(bbox, anchor_corners) {

bbox <- k_constant(bbox)

anchor_corners <- k_constant(anchor_corners)

intersection <- intersect(bbox, anchor_corners)

union <-

k_expand_dims(box_area(bbox), axis = 2) + k_expand_dims(box_area(anchor_corners), axis = 1) - intersection

res <- intersection / union

res %>% k_eval()

}

# compute intersection for IOU

intersect <- operate(box1, box2) {

box1_a <- box1[, 3:4] %>% k_expand_dims(axis = 2)

box2_a <- box2[, 3:4] %>% k_expand_dims(axis = 1)

max_xy <- k_minimum(box1_a, box2_a)

box1_b <- box1[, 1:2] %>% k_expand_dims(axis = 2)

box2_b <- box2[, 1:2] %>% k_expand_dims(axis = 1)

min_xy <- k_maximum(box1_b, box2_b)

intersection <- k_clip(max_xy - min_xy, min = 0, max = Inf)

intersection[, , 1] * intersection[, , 2]

}

box_area <- operate(field) {

(field[, 3] - field[, 1]) * (field[, 4] - field[, 2])

}By now you may be questioning – when does all this occur? Curiously, the instance we’re following, quick.ai’s object detection pocket book, does all this as a part of the loss calculation!

In TensorFlow, that is doable in precept (requiring some juggling of tf$cond, tf$while_loop and so forth., in addition to a little bit of creativity discovering replacements for non-differentiable operations).

However, easy information – just like the Keras loss operate anticipating the identical shapes for y_true and y_pred – made it not possible to observe the quick.ai strategy. As an alternative, all matching will happen within the knowledge generator.

Information generator

The generator has the acquainted construction, identified from the predecessor put up.

Right here is the whole code – we’ll speak by the main points instantly.

batch_size <- 16

image_size <- target_width # identical as top

threshold <- 0.4

class_background <- 21

ssd_generator <-

operate(knowledge,

target_height,

target_width,

shuffle,

batch_size) {

i <- 1

operate() {

if (shuffle) {

indices <- pattern(1:nrow(knowledge), measurement = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= nrow(knowledge))

i <<- 1

indices <- c(i:min(i + batch_size - 1, nrow(knowledge)))

i <<- i + size(indices)

}

x <-

array(0, dim = c(size(indices), target_height, target_width, 3))

y1 <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 16))

y2 <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 16, 4))

for (j in 1:size(indices)) {

x[j, , , ] <-

load_and_preprocess_image(knowledge[[indices[j], "file_name"]], target_height, target_width)

class_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$classes

xl_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$xl

yt_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$yt

xr_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$xr

yb_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$yb

lessons <- str_split(class_string, sample = ", ")[[1]]

xl <-

str_split(xl_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

yt <-

str_split(yt_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

xr <-

str_split(xr_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

yb <-

str_split(yb_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

# rows are objects, columns are coordinates (xl, yt, xr, yb)

# anchor_corners are 16 rows with corresponding coordinates

bbox <- cbind(xl, yt, xr, yb)

overlaps <- jaccard(bbox, anchor_corners)

c(gt_overlap, gt_idx) %<-% map_to_ground_truth(overlaps)

gt_class <- lessons[gt_idx]

pos <- gt_overlap > threshold

gt_class[gt_overlap < threshold] <- 21

# columns correspond to things

packing containers <- rbind(xl, yt, xr, yb)

# columns correspond to object packing containers based on gt_idx

gt_bbox <- packing containers[, gt_idx]

# set these with non-sufficient overlap to 0

gt_bbox[, !pos] <- 0

gt_bbox <- gt_bbox %>% t()

y1[j, ] <- as.integer(gt_class) - 1

y2[j, , ] <- gt_bbox

}

x <- x %>% imagenet_preprocess_input()

y1 <- y1 %>% to_categorical(num_classes = class_background)

checklist(x, checklist(y1, y2))

}

}Earlier than the generator can set off any calculations, it must first break up aside the a number of lessons and bounding field coordinates that are available one row of the dataset.

To make this extra concrete, we present what occurs for the “2 individuals and a couple of airplanes” picture we simply displayed.

We copy out code chunk-by-chunk from the generator so outcomes can really be displayed for inspection.

knowledge <- imageinfo4ssd

indices <- 1:8

j <- 5 # that is our picture

class_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$classes

xl_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$xl

yt_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$yt

xr_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$xr

yb_string <- knowledge[indices[j], ]$yb

lessons <- str_split(class_string, sample = ", ")[[1]]

xl <- str_split(xl_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

yt <- str_split(yt_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

xr <- str_split(xr_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)

yb <- str_split(yb_string, sample = ", ")[[1]] %>% as.double() %>% `/`(image_size)So listed here are that picture’s lessons:

[1] "1" "1" "15" "15"And its left bounding field coordinates:

[1] 0.20535714 0.26339286 0.38839286 0.04910714Now we will cbind these vectors collectively to acquire a object (bbox) the place rows are objects, and coordinates are within the columns:

# rows are objects, columns are coordinates (xl, yt, xr, yb)

bbox <- cbind(xl, yt, xr, yb)

bbox xl yt xr yb

[1,] 0.20535714 0.2723214 0.75000000 0.6473214

[2,] 0.26339286 0.3080357 0.39285714 0.4330357

[3,] 0.38839286 0.6383929 0.42410714 0.8125000

[4,] 0.04910714 0.6696429 0.08482143 0.8437500So we’re able to compute these packing containers’ overlap with the entire 16 grid cells. Recall that anchor_corners shops the grid cells in an identical method, the cells being within the rows and the coordinates within the columns.

# anchor_corners are 16 rows with corresponding coordinates

overlaps <- jaccard(bbox, anchor_corners)Now that we have now the overlaps, we will name the matching logic:

c(gt_overlap, gt_idx) %<-% map_to_ground_truth(overlaps)

gt_overlap [1] 0.00000000 0.03961473 0.04358353 1.99000000 0.00000000 1.99000000 1.99000000 0.03357313 0.00000000

[10] 0.27127662 0.16019417 0.00000000 0.00000000 0.00000000 0.00000000 0.00000000On the lookout for the worth 1.99 within the above – the worth indicating maximal, by the above standards, overlap of an object with a grid cell – we see that field 4 (counting in column-major order right here like R does) acquired matched (to an individual, as we’ll see quickly), field 6 did (to an airplane), and field 7 did (to an individual). How concerning the different airplane? It acquired misplaced within the matching.

This isn’t an issue of the matching algorithm although – it might disappear if we had multiple anchor field per grid cell.

On the lookout for the objects simply talked about within the class index, gt_idx, we see that certainly field 4 acquired matched to object 4 (an individual), field 6 acquired matched to object 2 (an airplane), and field 7 acquired matched to object 3 (the opposite individual):

[1] 1 1 4 4 1 2 3 3 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1By the way in which, don’t fear concerning the abundance of 1s right here. These are remnants from utilizing which.max to find out maximal overlap, and can disappear quickly.

As an alternative of pondering in object numbers, we must always suppose in object lessons (the respective numerical codes, that’s).

gt_class <- lessons[gt_idx]

gt_class [1] "1" "1" "15" "15" "1" "1" "15" "15" "1" "1" "1" "1" "1" "1" "1" "1"To date, we take note of even the very slightest overlap – of 0.1 p.c, say.

After all, this is unnecessary. We set all cells with an overlap < 0.4 to the background class:

pos <- gt_overlap > threshold

gt_class[gt_overlap < threshold] <- 21

gt_class[1] "21" "21" "21" "15" "21" "1" "15" "21" "21" "21" "21" "21" "21" "21" "21" "21"Now, to assemble the targets for studying, we have to put the mapping we discovered into an information construction.

The next provides us a 16×4 matrix of cells and the packing containers they’re accountable for:

xl yt xr yb

[1,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[2,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[3,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[4,] 0.04910714 0.6696429 0.08482143 0.8437500

[5,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[6,] 0.26339286 0.3080357 0.39285714 0.4330357

[7,] 0.38839286 0.6383929 0.42410714 0.8125000

[8,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[9,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[10,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[11,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[12,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[13,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[14,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[15,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000

[16,] 0.00000000 0.0000000 0.00000000 0.0000000Collectively, gt_bbox and gt_class make up the community’s studying targets.

y1[j, ] <- as.integer(gt_class) - 1

y2[j, , ] <- gt_bboxTo summarize, our goal is a listing of two outputs:

- the bounding field floor fact of dimensionality variety of grid cells instances variety of field coordinates, and

- the category floor fact of measurement variety of grid cells instances variety of lessons.

We will confirm this by asking the generator for a batch of inputs and targets:

[1] 16 16 21[1] 16 16 4Lastly, we’re prepared for the mannequin.

The mannequin

We begin from Resnet 50 as a characteristic extractor. This offers us tensors of measurement 7x7x2048.

feature_extractor <- application_resnet50(

include_top = FALSE,

input_shape = c(224, 224, 3)

)Then, we append a number of conv layers. Three of these layers are “simply” there for capability; the final one although has a extra process: By advantage of strides = 2, it downsamples its enter to from 7×7 to 4×4 within the top/width dimensions.

This decision of 4×4 provides us precisely the grid we’d like!

enter <- feature_extractor$enter

frequent <- feature_extractor$output %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_1"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_2"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_3"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

strides = 2,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv2"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() Now we will do as we did in that different put up, connect one output for the bounding packing containers and one for the lessons.

Observe how we don’t combination over the spatial grid although. As an alternative, we reshape it so the 4×4 grid cells seem sequentially.

Right here first is the category output. We have now 21 lessons (the 20 lessons from PASCAL, plus background), and we have to classify every cell. We thus find yourself with an output of measurement 16×21.

class_output <-

layer_conv_2d(

frequent,

filters = 21,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

title = "class_conv"

) %>%

layer_reshape(target_shape = c(16, 21), title = "class_output")For the bounding field output, we apply a tanh activation in order that values lie between -1 and 1. It is because they’re used to compute offsets to the grid cell facilities.

These computations occur within the layer_lambda. We begin from the precise anchor field facilities, and transfer them round by a scaled-down model of the activations.

We then convert these to anchor corners – identical as we did above with the bottom fact anchors, simply working on tensors, this time.

bbox_output <-

layer_conv_2d(

frequent,

filters = 4,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

title = "bbox_conv"

) %>%

layer_reshape(target_shape = c(16, 4), title = "bbox_flatten") %>%

layer_activation("tanh") %>%

layer_lambda(

f = operate(x) {

activation_centers <-

(x[, , 1:2] / 2 * gridsize) + k_constant(anchors[, 1:2])

activation_height_width <-

(x[, , 3:4] / 2 + 1) * k_constant(anchors[, 3:4])

activation_corners <-

k_concatenate(

checklist(

activation_centers - activation_height_width / 2,

activation_centers + activation_height_width / 2

)

)

activation_corners

},

title = "bbox_output"

)Now that we have now all layers, let’s rapidly end up the mannequin definition:

mannequin <- keras_model(

inputs = enter,

outputs = checklist(class_output, bbox_output)

)The final ingredient lacking, then, is the loss operate.

Loss

To the mannequin’s two outputs – a classification output and a regression output – correspond two losses, simply as within the fundamental classification + localization mannequin. Solely this time, we have now 16 grid cells to maintain.

Class loss makes use of tf$nn$sigmoid_cross_entropy_with_logits to compute the binary crossentropy between targets and unnormalized community activation, summing over grid cells and dividing by the variety of lessons.

# shapes are batch_size * 16 * 21

class_loss <- operate(y_true, y_pred) {

class_loss <-

tf$nn$sigmoid_cross_entropy_with_logits(labels = y_true, logits = y_pred)

class_loss <-

tf$reduce_sum(class_loss) / tf$forged(n_classes + 1, "float32")

class_loss

}Localization loss is calculated for all packing containers the place in actual fact there is an object current within the floor fact. All different activations get masked out.

The loss itself then is simply imply absolute error, scaled by a multiplier designed to deliver each loss elements to related magnitudes. In follow, it is smart to experiment a bit right here.

# shapes are batch_size * 16 * 4

bbox_loss <- operate(y_true, y_pred) {

# calculate localization loss for all packing containers the place floor fact was assigned some overlap

# calculate masks

pos <- y_true[, , 1] + y_true[, , 3] > 0

pos <-

pos %>% k_cast(tf$float32) %>% k_reshape(form = c(batch_size, 16, 1))

pos <-

tf$tile(pos, multiples = k_constant(c(1L, 1L, 4L), dtype = tf$int32))

diff <- y_pred - y_true

# masks out irrelevant activations

diff <- diff %>% tf$multiply(pos)

loc_loss <- diff %>% tf$abs() %>% tf$reduce_mean()

loc_loss * 100

}Above, we’ve already outlined the mannequin however we nonetheless must freeze the characteristic detector’s weights and compile it.

mannequin %>% freeze_weights()

mannequin %>% unfreeze_weights(from = "head_conv1_1")

mannequinAnd we’re prepared to coach. Coaching this mannequin may be very time consuming, such that for functions “in the actual world,” we would need to do optimize this system for reminiscence consumption and runtime.

Like we stated above, on this put up we’re actually specializing in understanding the strategy.

steps_per_epoch <- nrow(imageinfo4ssd) / batch_size

mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = steps_per_epoch,

epochs = 5,

callbacks = callback_model_checkpoint(

"weights.{epoch:02d}-{loss:.2f}.hdf5",

save_weights_only = TRUE

)

)After 5 epochs, that is what we get from the mannequin. It’s on the correct method, however it’ll want many extra epochs to achieve respectable efficiency.

Other than coaching for a lot of extra epochs, what might we do? We’ll wrap up the put up with two instructions for enchancment, however received’t implement them utterly.

The primary one really is fast to implement. Right here we go.

Focal loss

Above, we have been utilizing cross entropy for the classification loss. Let’s have a look at what that entails.

The determine exhibits loss incurred when the right reply is 1. We see that regardless that loss is highest when the community may be very flawed, it nonetheless incurs vital loss when it’s “proper for all sensible functions” – that means, its output is simply above 0.5.

In circumstances of robust class imbalance, this habits might be problematic. A lot coaching vitality is wasted on getting “much more proper” on circumstances the place the online is correct already – as will occur with situations of the dominant class. As an alternative, the community ought to dedicate extra effort to the exhausting circumstances – exemplars of the rarer lessons.

In object detection, the prevalent class is background – no class, actually. As an alternative of getting increasingly proficient at predicting background, the community had higher discover ways to inform aside the precise object lessons.

Another was identified by the authors of the RetinaNet paper(Lin et al. 2017): They launched a parameter (gamma) that leads to reducing loss for samples that have already got been properly categorized.

Totally different implementations are discovered on the web, in addition to completely different settings for the hyperparameters. Right here’s a direct port of the quick.ai code:

alpha <- 0.25

gamma <- 1

get_weights <- operate(y_true, y_pred) {

p <- y_pred %>% k_sigmoid()

pt <- y_true*p + (1-p)*(1-y_true)

w <- alpha*y_true + (1-alpha)*(1-y_true)

w <- w * (1-pt)^gamma

w

}

class_loss_focal <- operate(y_true, y_pred) {

w <- get_weights(y_true, y_pred)

cx <- tf$nn$sigmoid_cross_entropy_with_logits(labels = y_true, logits = y_pred)

weighted_cx <- w * cx

class_loss <-

tf$reduce_sum(weighted_cx) / tf$forged(21, "float32")

class_loss

}From testing this loss, it appears to yield higher efficiency, however doesn’t render out of date the necessity for substantive coaching time.

Lastly, let’s see what we’d should do if we wished to make use of a number of anchor packing containers per grid cells.

Extra anchor packing containers

The “actual SSD” has anchor packing containers of various side ratios, and it places detectors at completely different phases of the community. Let’s implement this.

Anchor field coordinates

We create anchor packing containers as combos of

anchor_zooms <- c(0.7, 1, 1.3)

anchor_zooms[1] 0.7 1.0 1.3 [,1] [,2]

[1,] 1.0 1.0

[2,] 1.0 0.5

[3,] 0.5 1.0On this instance, we have now 9 completely different combos:

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 0.70 0.70

[2,] 0.70 0.35

[3,] 0.35 0.70

[4,] 1.00 1.00

[5,] 1.00 0.50

[6,] 0.50 1.00

[7,] 1.30 1.30

[8,] 1.30 0.65

[9,] 0.65 1.30We place detectors at three phases. Resolutions might be 4×4 (as we had earlier than) and moreover, 2×2 and 1×1:

As soon as that’s been decided, we will compute

- x coordinates of the field facilities:

- y coordinates of the field facilities:

- the x-y representations of the facilities:

- the sizes of the bottom grids (0.25, 0.5, and 1):

- the centers-width-height representations of the anchor packing containers:

anchors <- cbind(anchor_centers, anchor_sizes)- and eventually, the corners illustration of the packing containers!

So right here, then, is a plot of the (distinct) field facilities: One within the center, for the 9 massive packing containers, 4 for the 4 * 9 medium-size packing containers, and 16 for the 16 * 9 small packing containers.

After all, even when we aren’t going to coach this model, we at the least must see these in motion!

How would a mannequin look that might take care of these?

Mannequin

Once more, we’d begin from a characteristic detector …

feature_extractor <- application_resnet50(

include_top = FALSE,

input_shape = c(224, 224, 3)

)… and fasten some customized conv layers.

enter <- feature_extractor$enter

frequent <- feature_extractor$output %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_1"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_2"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "head_conv1_3"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization()Then, issues get completely different. We need to connect detectors (= output layers) to completely different phases in a pipeline of successive downsamplings.

If that doesn’t name for the Keras purposeful API…

Right here’s the downsizing pipeline.

downscale_4x4 <- frequent %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

strides = 2,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "downscale_4x4"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() downscale_2x2 <- downscale_4x4 %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

strides = 2,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "downscale_2x2"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() downscale_1x1 <- downscale_2x2 %>%

layer_conv_2d(

filters = 256,

kernel_size = 3,

strides = 2,

padding = "identical",

activation = "relu",

title = "downscale_1x1"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() The bounding field output definitions get a bit of messier than earlier than, as every output has to take note of its relative anchor field coordinates.

create_bbox_output <- operate(prev_layer, anchor_start, anchor_stop, suffix) {

output <- layer_conv_2d(

prev_layer,

filters = 4 * ok,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical",

title = paste0("bbox_conv_", suffix)

) %>%

layer_reshape(target_shape = c(-1, 4), title = paste0("bbox_flatten_", suffix)) %>%

layer_activation("tanh") %>%

layer_lambda(

f = operate(x) {

activation_centers <-

(x[, , 1:2] / 2 * matrix(grid_sizes[anchor_start:anchor_stop], ncol = 1)) +

k_constant(anchors[anchor_start:anchor_stop, 1:2])

activation_height_width <-

(x[, , 3:4] / 2 + 1) * k_constant(anchors[anchor_start:anchor_stop, 3:4])

activation_corners <-

k_concatenate(

checklist(

activation_centers - activation_height_width / 2,

activation_centers + activation_height_width / 2

)

)

activation_corners

},

title = paste0("bbox_output_", suffix)

)

output

}Right here they’re: Each hooked up to it’s respective stage of motion within the pipeline.

bbox_output_4x4 <- create_bbox_output(downscale_4x4, 1, 144, "4x4")bbox_output_2x2 <- create_bbox_output(downscale_2x2, 145, 180, "2x2")bbox_output_1x1 <- create_bbox_output(downscale_1x1, 181, 189, "1x1")The identical precept applies to the category outputs.

class_output_4x4 <- create_class_output(downscale_4x4, "4x4")class_output_2x2 <- create_class_output(downscale_2x2, "2x2")class_output_1x1 <- create_class_output(downscale_1x1, "1x1")And glue all of it collectively, to get the mannequin.

mannequin <- keras_model(

inputs = enter,

outputs = checklist(

bbox_output_1x1,

bbox_output_2x2,

bbox_output_4x4,

class_output_1x1,

class_output_2x2,

class_output_4x4)

)Now, we are going to cease right here. To run this, there’s one other ingredient that must be adjusted: the information generator.

Our focus being on explaining the ideas although, we’ll go away that to the reader.

Conclusion

Whereas we haven’t ended up with a good-performing mannequin for object detection, we do hope that we’ve managed to shed some gentle on the thriller of object detection. What’s a bounding field? What’s an anchor (resp. prior, rep. default) field? How do you match them up in follow?

For those who’ve “simply” learn the papers (YOLO, SSD), however by no means seen any code, it might seem to be all actions occur in some wonderland past the horizon. They don’t. However coding them, as we’ve seen, might be cumbersome, even within the very fundamental variations we’ve applied. To carry out object detection in manufacturing, then, much more time must be spent on coaching and tuning fashions. However typically simply studying about how one thing works might be very satisfying.

Lastly, we’d once more prefer to stress how a lot this put up leans on what the quick.ai guys did. Their work most positively is enriching not simply the PyTorch, but in addition the R-TensorFlow neighborhood!