We’ve all turn out to be used to deep studying’s success in picture classification. Larger Swiss Mountain canine or Bernese mountain canine? Pink panda or large panda? No drawback.

Nevertheless, in actual life it’s not sufficient to call the only most salient object on an image. Prefer it or not, some of the compelling examples is autonomous driving: We don’t need the algorithm to acknowledge simply that automobile in entrance of us, but additionally the pedestrian about to cross the road. And, simply detecting the pedestrian just isn’t ample. The precise location of objects issues.

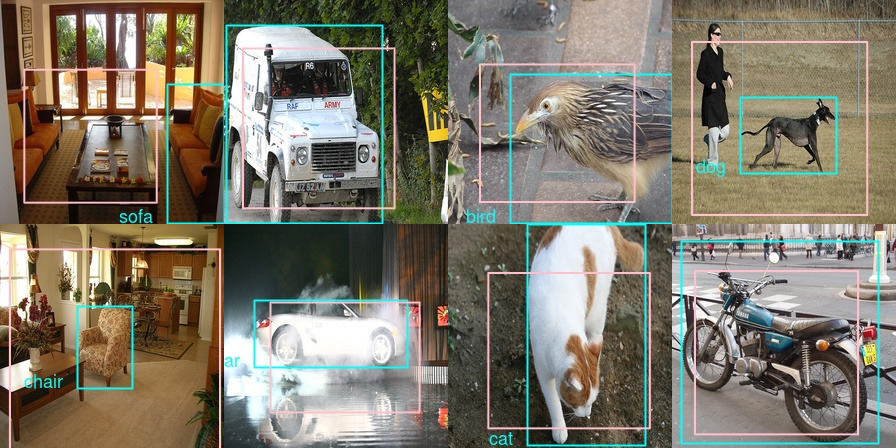

The time period object detection is often used to seek advice from the duty of naming and localizing a number of objects in a picture body. Object detection is tough; we’ll construct as much as it in a free sequence of posts, specializing in ideas as an alternative of aiming for final efficiency. Immediately, we’ll begin with a number of easy constructing blocks: Classification, each single and a number of; localization; and mixing each classification and localization of a single object.

Dataset

We’ll be utilizing photographs and annotations from the Pascal VOC dataset which may be downloaded from this mirror.

Particularly, we’ll use knowledge from the 2007 problem and the identical JSON annotation file as used within the quick.ai course.

Fast obtain/group directions, shamelessly taken from a useful submit on the quick.ai wiki, are as follows:

# mkdir knowledge && cd knowledge

# curl -OL http://pjreddie.com/media/recordsdata/VOCtrainval_06-Nov-2007.tar

# curl -OL https://storage.googleapis.com/coco-dataset/exterior/PASCAL_VOC.zip

# tar -xf VOCtrainval_06-Nov-2007.tar

# unzip PASCAL_VOC.zip

# mv PASCAL_VOC/*.json .

# rmdir PASCAL_VOC

# tar -xvf VOCtrainval_06-Nov-2007.tarIn phrases, we take the pictures and the annotation file from totally different locations:

Whether or not you’re executing the listed instructions or arranging recordsdata manually, you must ultimately find yourself with directories/recordsdata analogous to those:

img_dir <- "knowledge/VOCdevkit/VOC2007/JPEGImages"

annot_file <- "knowledge/pascal_train2007.json"Now we have to extract some info from that json file.

Preprocessing

Let’s rapidly be sure we have now all required libraries loaded.

Annotations comprise details about three varieties of issues we’re enthusiastic about.

annotations <- fromJSON(file = annot_file)

str(annotations, max.degree = 1)Checklist of 4

$ photographs :Checklist of 2501

$ sort : chr "situations"

$ annotations:Checklist of 7844

$ classes :Checklist of 20First, traits of the picture itself (peak and width) and the place it’s saved. Not surprisingly, right here it’s one entry per picture.

Then, object class ids and bounding field coordinates. There could also be a number of of those per picture.

In Pascal VOC, there are 20 object courses, from ubiquitous autos (automobile, aeroplane) over indispensable animals (cat, sheep) to extra uncommon (in widespread datasets) varieties like potted plant or television monitor.

courses <- c(

"aeroplane",

"bicycle",

"hen",

"boat",

"bottle",

"bus",

"automobile",

"cat",

"chair",

"cow",

"diningtable",

"canine",

"horse",

"bike",

"particular person",

"pottedplant",

"sheep",

"couch",

"practice",

"tvmonitor"

)

boxinfo <- annotations$annotations %>% {

tibble(

image_id = map_dbl(., "image_id"),

category_id = map_dbl(., "category_id"),

bbox = map(., "bbox")

)

}The bounding bins at the moment are saved in a listing column and have to be unpacked.

For the bounding bins, the annotation file supplies x_left and y_top coordinates, in addition to width and peak.

We are going to largely be working with nook coordinates, so we create the lacking x_right and y_bottom.

As traditional in picture processing, the y axis begins from the highest.

Lastly, we nonetheless have to match class ids to class names.

So, placing all of it collectively:

Be aware that right here nonetheless, we have now a number of entries per picture, every annotated object occupying its personal row.

There’s one step that can bitterly harm our localization efficiency if we later neglect it, so let’s do it now already: We have to scale all bounding field coordinates in keeping with the precise picture measurement we’ll use once we cross it to our community.

target_height <- 224

target_width <- 224

imageinfo <- imageinfo %>% mutate(

x_left_scaled = (x_left / image_width * target_width) %>% spherical(),

x_right_scaled = (x_right / image_width * target_width) %>% spherical(),

y_top_scaled = (y_top / image_height * target_height) %>% spherical(),

y_bottom_scaled = (y_bottom / image_height * target_height) %>% spherical(),

bbox_width_scaled = (bbox_width / image_width * target_width) %>% spherical(),

bbox_height_scaled = (bbox_height / image_height * target_height) %>% spherical()

)Let’s take a look at our knowledge. Selecting one of many early entries and displaying the unique picture along with the thing annotation yields

img_data <- imageinfo[4,]

img <- image_read(file.path(img_dir, img_data$file_name))

img <- image_draw(img)

rect(

img_data$x_left,

img_data$y_bottom,

img_data$x_right,

img_data$y_top,

border = "white",

lwd = 2

)

textual content(

img_data$x_left,

img_data$y_top,

img_data$identify,

offset = 1,

pos = 2,

cex = 1.5,

col = "white"

)

dev.off()

Now as indicated above, on this submit we’ll largely handle dealing with a single object in a picture. This implies we have now to resolve, per picture, which object to single out.

An inexpensive technique appears to be selecting the thing with the biggest floor fact bounding field.

After this operation, we solely have 2501 photographs to work with – not many in any respect! For classification, we might merely use knowledge augmentation as offered by Keras, however to work with localization we’d must spin our personal augmentation algorithm.

We’ll go away this to a later event and for now, give attention to the fundamentals.

Lastly after train-test cut up

train_indices <- pattern(1:n_samples, 0.8 * n_samples)

train_data <- imageinfo_maxbb[train_indices,]

validation_data <- imageinfo_maxbb[-train_indices,]our coaching set consists of 2000 photographs with one annotation every. We’re prepared to start out coaching, and we’ll begin gently, with single-object classification.

Single-object classification

In all instances, we’ll use XCeption as a primary characteristic extractor. Having been skilled on ImageNet, we don’t count on a lot effective tuning to be essential to adapt to Pascal VOC, so we go away XCeption’s weights untouched

and put just some customized layers on prime.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

feature_extractor %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(models = 512, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.5) %>%

layer_dense(models = 20, activation = "softmax")

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "sparse_categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = checklist("accuracy")

)How ought to we cross our knowledge to Keras? We might easy use Keras’ image_data_generator, however given we’ll want customized turbines quickly, we’ll construct a easy one ourselves.

This one delivers photographs in addition to the corresponding targets in a stream. Be aware how the targets aren’t one-hot-encoded, however integers – utilizing sparse_categorical_crossentropy as a loss perform allows this comfort.

batch_size <- 10

load_and_preprocess_image <- perform(image_name, target_height, target_width) {

img_array <- image_load(

file.path(img_dir, image_name),

target_size = c(target_height, target_width)

) %>%

image_to_array() %>%

xception_preprocess_input()

dim(img_array) <- c(1, dim(img_array))

img_array

}

classification_generator <-

perform(knowledge,

target_height,

target_width,

shuffle,

batch_size) {

i <- 1

perform() {

if (shuffle) {

indices <- pattern(1:nrow(knowledge), measurement = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= nrow(knowledge))

i <<- 1

indices <- c(i:min(i + batch_size - 1, nrow(knowledge)))

i <<- i + size(indices)

}

x <-

array(0, dim = c(size(indices), target_height, target_width, 3))

y <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 1))

for (j in 1:size(indices)) {

x[j, , , ] <-

load_and_preprocess_image(knowledge[[indices[j], "file_name"]],

target_height, target_width)

y[j, ] <-

knowledge[[indices[j], "category_id"]] - 1

}

x <- x / 255

checklist(x, y)

}

}

train_gen <- classification_generator(

train_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = TRUE,

batch_size = batch_size

)

valid_gen <- classification_generator(

validation_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = FALSE,

batch_size = batch_size

)Now how does coaching go?

mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

epochs = 20,

steps_per_epoch = nrow(train_data) / batch_size,

validation_data = valid_gen,

validation_steps = nrow(validation_data) / batch_size,

callbacks = checklist(

callback_model_checkpoint(

file.path("class_only", "weights.{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}.hdf5")

),

callback_early_stopping(endurance = 2)

)

)For us, after 8 epochs, accuracies on the practice resp. validation units have been at 0.68 and 0.74, respectively. Not too unhealthy given given we’re attempting to distinguish between 20 courses right here.

Now let’s rapidly suppose what we’d change if we have been to categorise a number of objects in a single picture. Modifications largely concern preprocessing steps.

A number of object classification

This time, we multi-hot-encode our knowledge. For each picture (as represented by its filename), right here we have now a vector of size 20 the place 0 signifies absence, 1 means presence of the respective object class:

image_cats <- imageinfo %>%

choose(category_id) %>%

mutate(category_id = category_id - 1) %>%

pull() %>%

to_categorical(num_classes = 20)

image_cats <- knowledge.body(image_cats) %>%

add_column(file_name = imageinfo$file_name, .earlier than = TRUE)

image_cats <- image_cats %>%

group_by(file_name) %>%

summarise_all(.funs = funs(max))

n_samples <- nrow(image_cats)

train_indices <- pattern(1:n_samples, 0.8 * n_samples)

train_data <- image_cats[train_indices,]

validation_data <- image_cats[-train_indices,]Correspondingly, we modify the generator to return a goal of dimensions batch_size * 20, as an alternative of batch_size * 1.

classification_generator <-

perform(knowledge,

target_height,

target_width,

shuffle,

batch_size) {

i <- 1

perform() {

if (shuffle) {

indices <- pattern(1:nrow(knowledge), measurement = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= nrow(knowledge))

i <<- 1

indices <- c(i:min(i + batch_size - 1, nrow(knowledge)))

i <<- i + size(indices)

}

x <-

array(0, dim = c(size(indices), target_height, target_width, 3))

y <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 20))

for (j in 1:size(indices)) {

x[j, , , ] <-

load_and_preprocess_image(knowledge[[indices[j], "file_name"]],

target_height, target_width)

y[j, ] <-

knowledge[indices[j], 2:21] %>% as.matrix()

}

x <- x / 255

checklist(x, y)

}

}

train_gen <- classification_generator(

train_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = TRUE,

batch_size = batch_size

)

valid_gen <- classification_generator(

validation_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = FALSE,

batch_size = batch_size

)Now, probably the most fascinating change is to the mannequin – regardless that it’s a change to 2 traces solely.

Had been we to make use of categorical_crossentropy now (the non-sparse variant of the above), mixed with a softmax activation, we’d successfully inform the mannequin to select only one, specifically, probably the most possible object.

As a substitute, we need to resolve: For every object class, is it current within the picture or not? Thus, as an alternative of softmax we use sigmoid, paired with binary_crossentropy, to acquire an impartial verdict on each class.

feature_extractor <-

application_xception(

include_top = FALSE,

input_shape = c(224, 224, 3),

pooling = "avg"

)

feature_extractor %>% freeze_weights()

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

feature_extractor %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(models = 512, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.5) %>%

layer_dense(models = 20, activation = "sigmoid")

mannequin %>% compile(optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = checklist("accuracy"))And eventually, once more, we match the mannequin:

mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

epochs = 20,

steps_per_epoch = nrow(train_data) / batch_size,

validation_data = valid_gen,

validation_steps = nrow(validation_data) / batch_size,

callbacks = checklist(

callback_model_checkpoint(

file.path("multiclass", "weights.{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}.hdf5")

),

callback_early_stopping(endurance = 2)

)

)This time, (binary) accuracy surpasses 0.95 after one epoch already, on each the practice and validation units. Not surprisingly, accuracy is considerably larger right here than once we needed to single out certainly one of 20 courses (and that, with different confounding objects current generally!).

Now, likelihood is that in the event you’ve achieved any deep studying earlier than, you’ve achieved picture classification in some type, maybe even within the multiple-object variant. To construct up within the route of object detection, it’s time we add a brand new ingredient: localization.

Single-object localization

From right here on, we’re again to coping with a single object per picture. So the query now’s, how will we study bounding bins?

In case you’ve by no means heard of this, the reply will sound unbelievably easy (naive even): We formulate this as a regression drawback and goal to foretell the precise coordinates. To set real looking expectations – we certainly shouldn’t count on final precision right here. However in a approach it’s wonderful it does even work in any respect.

What does this imply, formulate as a regression drawback? Concretely, it means we’ll have a dense output layer with 4 models, every akin to a nook coordinate.

So let’s begin with the mannequin this time. Once more, we use Xception, however there’s an vital distinction right here: Whereas earlier than, we mentioned pooling = "avg" to acquire an output tensor of dimensions batch_size * variety of filters, right here we don’t do any averaging or flattening out of the spatial grid. It’s because it’s precisely the spatial info we’re enthusiastic about!

For Xception, the output decision can be 7×7. So a priori, we shouldn’t count on excessive precision on objects a lot smaller than about 32×32 pixels (assuming the usual enter measurement of 224×224).

Now we append our customized regression module.

We are going to practice with one of many loss capabilities frequent in regression duties, imply absolute error. However in duties like object detection or segmentation, we’re additionally enthusiastic about a extra tangible amount: How a lot do estimate and floor fact overlap?

Overlap is often measured as Intersection over Union, or Jaccard distance. Intersection over Union is precisely what it says, a ratio between house shared by the objects and house occupied once we take them collectively.

To evaluate the mannequin’s progress, we will simply code this as a customized metric:

metric_iou <- perform(y_true, y_pred) {

# order is [x_left, y_top, x_right, y_bottom]

intersection_xmin <- k_maximum(y_true[ ,1], y_pred[ ,1])

intersection_ymin <- k_maximum(y_true[ ,2], y_pred[ ,2])

intersection_xmax <- k_minimum(y_true[ ,3], y_pred[ ,3])

intersection_ymax <- k_minimum(y_true[ ,4], y_pred[ ,4])

area_intersection <- (intersection_xmax - intersection_xmin) *

(intersection_ymax - intersection_ymin)

area_y <- (y_true[ ,3] - y_true[ ,1]) * (y_true[ ,4] - y_true[ ,2])

area_yhat <- (y_pred[ ,3] - y_pred[ ,1]) * (y_pred[ ,4] - y_pred[ ,2])

area_union <- area_y + area_yhat - area_intersection

iou <- area_intersection/area_union

k_mean(iou)

}Mannequin compilation then goes like

Now modify the generator to return bounding field coordinates as targets…

localization_generator <-

perform(knowledge,

target_height,

target_width,

shuffle,

batch_size) {

i <- 1

perform() {

if (shuffle) {

indices <- pattern(1:nrow(knowledge), measurement = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= nrow(knowledge))

i <<- 1

indices <- c(i:min(i + batch_size - 1, nrow(knowledge)))

i <<- i + size(indices)

}

x <-

array(0, dim = c(size(indices), target_height, target_width, 3))

y <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 4))

for (j in 1:size(indices)) {

x[j, , , ] <-

load_and_preprocess_image(knowledge[[indices[j], "file_name"]],

target_height, target_width)

y[j, ] <-

knowledge[indices[j], c("x_left_scaled",

"y_top_scaled",

"x_right_scaled",

"y_bottom_scaled")] %>% as.matrix()

}

x <- x / 255

checklist(x, y)

}

}

train_gen <- localization_generator(

train_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = TRUE,

batch_size = batch_size

)

valid_gen <- localization_generator(

validation_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = FALSE,

batch_size = batch_size

)… and we’re able to go!

mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

epochs = 20,

steps_per_epoch = nrow(train_data) / batch_size,

validation_data = valid_gen,

validation_steps = nrow(validation_data) / batch_size,

callbacks = checklist(

callback_model_checkpoint(

file.path("loc_only", "weights.{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}.hdf5")

),

callback_early_stopping(endurance = 2)

)

)After 8 epochs, IOU on each coaching and take a look at units is round 0.35. This quantity doesn’t look too good. To study extra about how coaching went, we have to see some predictions. Right here’s a comfort perform that shows a picture, the bottom fact field of probably the most salient object (as outlined above), and if given, class and bounding field predictions.

plot_image_with_boxes <- perform(file_name,

object_class,

field,

scaled = FALSE,

class_pred = NULL,

box_pred = NULL) {

img <- image_read(file.path(img_dir, file_name))

if(scaled) img <- image_resize(img, geometry = "224x224!")

img <- image_draw(img)

x_left <- field[1]

y_bottom <- field[2]

x_right <- field[3]

y_top <- field[4]

rect(

x_left,

y_bottom,

x_right,

y_top,

border = "cyan",

lwd = 2.5

)

textual content(

x_left,

y_top,

object_class,

offset = 1,

pos = 2,

cex = 1.5,

col = "cyan"

)

if (!is.null(box_pred))

rect(box_pred[1],

box_pred[2],

box_pred[3],

box_pred[4],

border = "yellow",

lwd = 2.5)

if (!is.null(class_pred))

textual content(

box_pred[1],

box_pred[2],

class_pred,

offset = 0,

pos = 4,

cex = 1.5,

col = "yellow")

dev.off()

img %>% image_write(paste0("preds_", file_name))

plot(img)

}First, let’s see predictions on pattern photographs from the coaching set.

train_1_8 <- train_data[1:8, c("file_name",

"name",

"x_left_scaled",

"y_top_scaled",

"x_right_scaled",

"y_bottom_scaled")]

for (i in 1:8) {

preds <-

mannequin %>% predict(

load_and_preprocess_image(train_1_8[i, "file_name"],

target_height, target_width),

batch_size = 1

)

plot_image_with_boxes(train_1_8$file_name[i],

train_1_8$identify[i],

train_1_8[i, 3:6] %>% as.matrix(),

scaled = TRUE,

box_pred = preds)

}

As you’d guess from trying, the cyan-colored bins are the bottom fact ones. Now trying on the predictions explains lots concerning the mediocre IOU values! Let’s take the very first pattern picture – we wished the mannequin to give attention to the couch, nevertheless it picked the desk, which can also be a class within the dataset (though within the type of eating desk). Comparable with the picture on the correct of the primary row – we wished to it to select simply the canine nevertheless it included the particular person, too (by far probably the most regularly seen class within the dataset).

So we truly made the duty much more tough than had we stayed with e.g., ImageNet the place usually a single object is salient.

Now test predictions on the validation set.

Once more, we get the same impression: The mannequin did study one thing, however the process is ailing outlined. Have a look at the third picture in row 2: Isn’t it fairly consequent the mannequin picks all individuals as an alternative of singling out some particular man?

If single-object localization is that simple, how technically concerned can it’s to output a category label on the identical time?

So long as we stick with a single object, the reply certainly is: not a lot.

Let’s end up at present with a constrained mixture of classification and localization: detection of a single object.

Single-object detection

Combining regression and classification into one means we’ll need to have two outputs in our mannequin.

We’ll thus use the purposeful API this time.

In any other case, there isn’t a lot new right here: We begin with an XCeption output of spatial decision 7×7, append some customized processing and return two outputs, one for bounding field regression and one for classification.

feature_extractor <- application_xception(

include_top = FALSE,

input_shape = c(224, 224, 3)

)

enter <- feature_extractor$enter

frequent <- feature_extractor$output %>%

layer_flatten(identify = "flatten") %>%

layer_activation_relu() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(models = 512, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(charge = 0.5)

regression_output <-

layer_dense(frequent, models = 4, identify = "regression_output")

class_output <- layer_dense(

frequent,

models = 20,

activation = "softmax",

identify = "class_output"

)

mannequin <- keras_model(

inputs = enter,

outputs = checklist(regression_output, class_output)

)When defining the losses (imply absolute error and categorical crossentropy, simply as within the respective single duties of regression and classification), we might weight them so that they find yourself on roughly a typical scale. Actually that didn’t make a lot of a distinction so we present the respective code in commented type.

mannequin %>% freeze_weights(to = "flatten")

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = checklist("mae", "sparse_categorical_crossentropy"),

#loss_weights = checklist(

# regression_output = 0.05,

# class_output = 0.95),

metrics = checklist(

regression_output = custom_metric("iou", metric_iou),

class_output = "accuracy"

)

)Identical to mannequin outputs and losses are each lists, the info generator has to return the bottom fact samples in a listing.

Becoming the mannequin then goes as traditional.

loc_class_generator <-

perform(knowledge,

target_height,

target_width,

shuffle,

batch_size) {

i <- 1

perform() {

if (shuffle) {

indices <- pattern(1:nrow(knowledge), measurement = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= nrow(knowledge))

i <<- 1

indices <- c(i:min(i + batch_size - 1, nrow(knowledge)))

i <<- i + size(indices)

}

x <-

array(0, dim = c(size(indices), target_height, target_width, 3))

y1 <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 4))

y2 <- array(0, dim = c(size(indices), 1))

for (j in 1:size(indices)) {

x[j, , , ] <-

load_and_preprocess_image(knowledge[[indices[j], "file_name"]],

target_height, target_width)

y1[j, ] <-

knowledge[indices[j], c("x_left", "y_top", "x_right", "y_bottom")]

%>% as.matrix()

y2[j, ] <-

knowledge[[indices[j], "category_id"]] - 1

}

x <- x / 255

checklist(x, checklist(y1, y2))

}

}

train_gen <- loc_class_generator(

train_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = TRUE,

batch_size = batch_size

)

valid_gen <- loc_class_generator(

validation_data,

target_height = target_height,

target_width = target_width,

shuffle = FALSE,

batch_size = batch_size

)

mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

epochs = 20,

steps_per_epoch = nrow(train_data) / batch_size,

validation_data = valid_gen,

validation_steps = nrow(validation_data) / batch_size,

callbacks = checklist(

callback_model_checkpoint(

file.path("loc_class", "weights.{epoch:02d}-{val_loss:.2f}.hdf5")

),

callback_early_stopping(endurance = 2)

)

)What about mannequin predictions? A priori we would count on the bounding bins to look higher than within the regression-only mannequin, as a major a part of the mannequin is shared between classification and localization. Intuitively, I ought to be capable to extra exactly point out the boundaries of one thing if I’ve an concept what that one thing is.

Sadly, that didn’t fairly occur. The mannequin has turn out to be very biased to detecting a particular person all over the place, which is perhaps advantageous (considering security) in an autonomous driving software however isn’t fairly what we’d hoped for right here.

Simply to double-check this actually has to do with class imbalance, listed below are the precise frequencies:

imageinfo %>% group_by(identify)

%>% summarise(cnt = n())

%>% organize(desc(cnt))# A tibble: 20 x 2

identify cnt

<chr> <int>

1 particular person 2705

2 automobile 826

3 chair 726

4 bottle 338

5 pottedplant 305

6 hen 294

7 canine 271

8 couch 218

9 boat 208

10 horse 207

11 bicycle 202

12 bike 193

13 cat 191

14 sheep 191

15 tvmonitor 191

16 cow 185

17 practice 158

18 aeroplane 156

19 diningtable 148

20 bus 131To get higher efficiency, we’d have to discover a profitable strategy to cope with this. Nevertheless, dealing with class imbalance in deep studying is a subject of its personal, and right here we need to construct up within the route of objection detection. So we’ll make a minimize right here and in an upcoming submit, take into consideration how we will classify and localize a number of objects in a picture.

Conclusion

We’ve got seen that single-object classification and localization are conceptually easy. The large query now’s, are these approaches extensible to a number of objects? Or will new concepts have to come back in? We’ll observe up on this giving a brief overview of approaches after which, singling in on a type of and implementing it.