Introduction

On this publish we’ll describe how you can use smartphone accelerometer and gyroscope knowledge to foretell the bodily actions of the people carrying the telephones. The information used on this publish comes from the Smartphone-Based mostly Recognition of Human Actions and Postural Transitions Knowledge Set distributed by the College of California, Irvine. Thirty people have been tasked with performing numerous fundamental actions with an hooked up smartphone recording motion utilizing an accelerometer and gyroscope.

Earlier than we start, let’s load the varied libraries that we’ll use within the evaluation:

library(keras) # Neural Networks

library(tidyverse) # Knowledge cleansing / Visualization

library(knitr) # Desk printing

library(rmarkdown) # Misc. output utilities

library(ggridges) # VisualizationActions dataset

The information used on this publish come from the Smartphone-Based mostly Recognition of Human Actions and Postural Transitions Knowledge Set(Reyes-Ortiz et al. 2016) distributed by the College of California, Irvine.

When downloaded from the hyperlink above, the information comprises two completely different ‘components.’ One which has been pre-processed utilizing numerous function extraction strategies reminiscent of fast-fourier rework, and one other RawData part that merely provides the uncooked X,Y,Z instructions of an accelerometer and gyroscope. None of the usual noise filtering or function extraction utilized in accelerometer knowledge has been utilized. That is the information set we are going to use.

The motivation for working with the uncooked knowledge on this publish is to assist the transition of the code/ideas to time collection knowledge in much less well-characterized domains. Whereas a extra correct mannequin may very well be made by using the filtered/cleaned knowledge offered, the filtering and transformation can range drastically from process to process; requiring a lot of handbook effort and area data. One of many stunning issues about deep studying is the function extraction is realized from the information, not outdoors data.

Exercise labels

The information has integer encodings for the actions which, whereas not necessary to the mannequin itself, are useful to be used to see. Let’s load them first.

activityLabels <- learn.desk("knowledge/activity_labels.txt",

col.names = c("quantity", "label"))

activityLabels %>% kable(align = c("c", "l"))| 1 | WALKING |

| 2 | WALKING_UPSTAIRS |

| 3 | WALKING_DOWNSTAIRS |

| 4 | SITTING |

| 5 | STANDING |

| 6 | LAYING |

| 7 | STAND_TO_SIT |

| 8 | SIT_TO_STAND |

| 9 | SIT_TO_LIE |

| 10 | LIE_TO_SIT |

| 11 | STAND_TO_LIE |

| 12 | LIE_TO_STAND |

Subsequent, we load within the labels key for the RawData. This file is an inventory of all the observations, or particular person exercise recordings, contained within the knowledge set. The important thing for the columns is taken from the information README.txt.

Column 1: experiment quantity ID,

Column 2: consumer quantity ID,

Column 3: exercise quantity ID

Column 4: Label begin level

Column 5: Label finish level The beginning and finish factors are in variety of sign log samples (recorded at 50hz).

Let’s check out the primary 50 rows:

labels <- learn.desk(

"knowledge/RawData/labels.txt",

col.names = c("experiment", "userId", "exercise", "startPos", "endPos")

)

labels %>%

head(50) %>%

paged_table()File names

Subsequent, let’s take a look at the precise recordsdata of the consumer knowledge offered to us in RawData/

dataFiles <- checklist.recordsdata("knowledge/RawData")

dataFiles %>% head()

[1] "acc_exp01_user01.txt" "acc_exp02_user01.txt"

[3] "acc_exp03_user02.txt" "acc_exp04_user02.txt"

[5] "acc_exp05_user03.txt" "acc_exp06_user03.txt"There’s a three-part file naming scheme. The primary half is the kind of knowledge the file comprises: both acc for accelerometer or gyro for gyroscope. Subsequent is the experiment quantity, and final is the consumer Id for the recording. Let’s load these right into a dataframe for ease of use later.

fileInfo <- data_frame(

filePath = dataFiles

) %>%

filter(filePath != "labels.txt") %>%

separate(filePath, sep = '_',

into = c("sort", "experiment", "userId"),

take away = FALSE) %>%

mutate(

experiment = str_remove(experiment, "exp"),

userId = str_remove_all(userId, "consumer|.txt")

) %>%

unfold(sort, filePath)

fileInfo %>% head() %>% kable()| 01 | 01 | acc_exp01_user01.txt | gyro_exp01_user01.txt |

| 02 | 01 | acc_exp02_user01.txt | gyro_exp02_user01.txt |

| 03 | 02 | acc_exp03_user02.txt | gyro_exp03_user02.txt |

| 04 | 02 | acc_exp04_user02.txt | gyro_exp04_user02.txt |

| 05 | 03 | acc_exp05_user03.txt | gyro_exp05_user03.txt |

| 06 | 03 | acc_exp06_user03.txt | gyro_exp06_user03.txt |

Studying and gathering knowledge

Earlier than we will do something with the information offered we have to get it right into a model-friendly format. This implies we need to have an inventory of observations, their class (or exercise label), and the information comparable to the recording.

To acquire this we are going to scan by every of the recording recordsdata current in dataFiles, lookup what observations are contained within the recording, extract these recordings and return all the things to a straightforward to mannequin with dataframe.

# Learn contents of single file to a dataframe with accelerometer and gyro knowledge.

readInData <- operate(experiment, userId){

genFilePath = operate(sort) {

paste0("knowledge/RawData/", sort, "_exp",experiment, "_user", userId, ".txt")

}

bind_cols(

learn.desk(genFilePath("acc"), col.names = c("a_x", "a_y", "a_z")),

learn.desk(genFilePath("gyro"), col.names = c("g_x", "g_y", "g_z"))

)

}

# Perform to learn a given file and get the observations contained alongside

# with their lessons.

loadFileData <- operate(curExperiment, curUserId) {

# load sensor knowledge from file into dataframe

allData <- readInData(curExperiment, curUserId)

extractObservation <- operate(startPos, endPos){

allData[startPos:endPos,]

}

# get statement places on this file from labels dataframe

dataLabels <- labels %>%

filter(userId == as.integer(curUserId),

experiment == as.integer(curExperiment))

# extract observations as dataframes and save as a column in dataframe.

dataLabels %>%

mutate(

knowledge = map2(startPos, endPos, extractObservation)

) %>%

choose(-startPos, -endPos)

}

# scan by all experiment and userId combos and collect knowledge right into a dataframe.

allObservations <- map2_df(fileInfo$experiment, fileInfo$userId, loadFileData) %>%

right_join(activityLabels, by = c("exercise" = "quantity")) %>%

rename(activityName = label)

# cache work.

write_rds(allObservations, "allObservations.rds")

allObservations %>% dim()Exploring the information

Now that we now have all the information loaded together with the experiment, userId, and exercise labels, we will discover the information set.

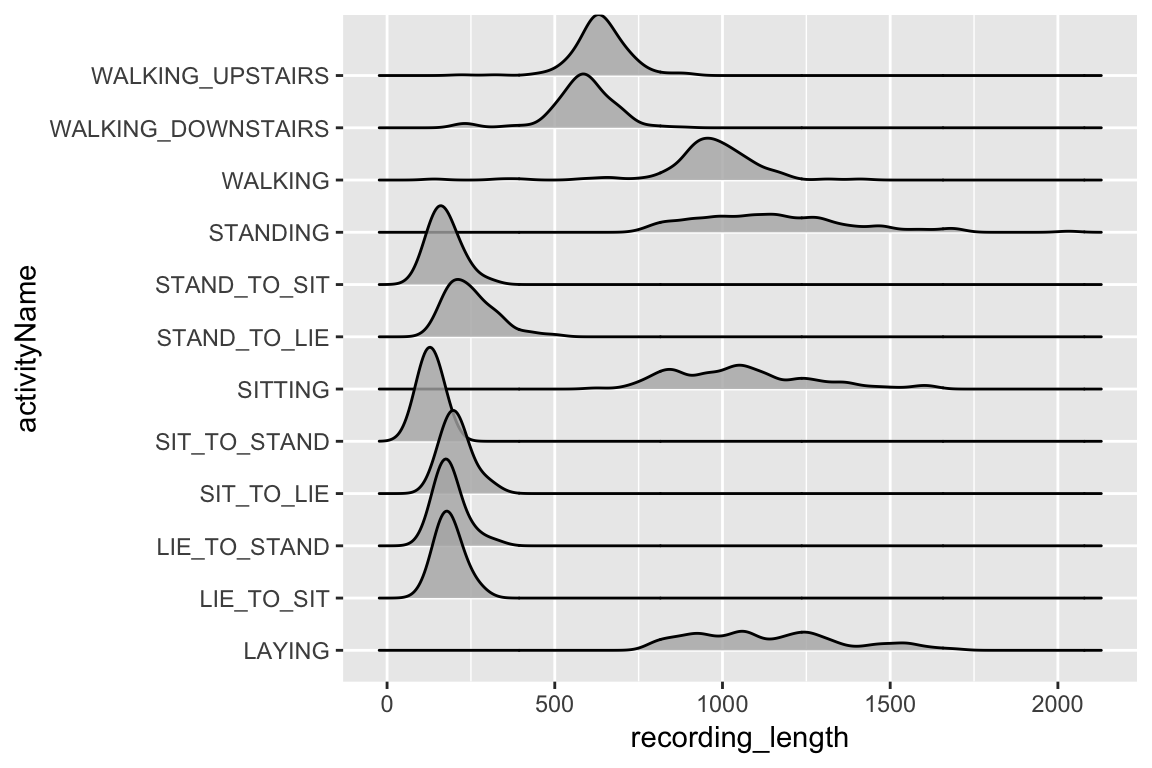

Size of recordings

Let’s first take a look at the size of the recordings by exercise.

allObservations %>%

mutate(recording_length = map_int(knowledge,nrow)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = recording_length, y = activityName)) +

geom_density_ridges(alpha = 0.8)

The very fact there’s such a distinction in size of recording between the completely different exercise sorts requires us to be a bit cautious with how we proceed. If we prepare the mannequin on each class directly we’re going to need to pad all of the observations to the size of the longest, which would depart a big majority of the observations with an enormous proportion of their knowledge being simply padding-zeros. Due to this, we are going to match our mannequin to simply the most important ‘group’ of observations size actions, these embody STAND_TO_SIT, STAND_TO_LIE, SIT_TO_STAND, SIT_TO_LIE, LIE_TO_STAND, and LIE_TO_SIT.

An attention-grabbing future course could be making an attempt to make use of one other structure reminiscent of an RNN that may deal with variable size inputs and coaching it on all the information. Nevertheless, you’ll run the danger of the mannequin studying merely that if the statement is lengthy it’s most definitely one of many 4 longest lessons which might not generalize to a state of affairs the place you have been operating this mannequin on a real-time-stream of information.

Filtering actions

Based mostly on our work from above, let’s subset the information to simply be of the actions of curiosity.

desiredActivities <- c(

"STAND_TO_SIT", "SIT_TO_STAND", "SIT_TO_LIE",

"LIE_TO_SIT", "STAND_TO_LIE", "LIE_TO_STAND"

)

filteredObservations <- allObservations %>%

filter(activityName %in% desiredActivities) %>%

mutate(observationId = 1:n())

filteredObservations %>% paged_table()So after our aggressive pruning of the information we may have a decent quantity of information left upon which our mannequin can study.

Coaching/testing cut up

Earlier than we go any additional into exploring the information for our mannequin, in an try and be as truthful as attainable with our efficiency measures, we have to cut up the information right into a prepare and take a look at set. Since every consumer carried out all actions simply as soon as (except for one who solely did 10 of the 12 actions) by splitting on userId we are going to make sure that our mannequin sees new individuals completely after we take a look at it.

# get all customers

userIds <- allObservations$userId %>% distinctive()

# randomly select 24 (80% of 30 people) for coaching

set.seed(42) # seed for reproducibility

trainIds <- pattern(userIds, dimension = 24)

# set the remainder of the customers to the testing set

testIds <- setdiff(userIds,trainIds)

# filter knowledge.

trainData <- filteredObservations %>%

filter(userId %in% trainIds)

testData <- filteredObservations %>%

filter(userId %in% testIds)Visualizing actions

Now that we now have trimmed our knowledge by eradicating actions and splitting off a take a look at set, we will truly visualize the information for every class to see if there’s any instantly discernible form that our mannequin could possibly choose up on.

First let’s unpack our knowledge from its dataframe of one-row-per-observation to a tidy model of all of the observations.

unpackedObs <- 1:nrow(trainData) %>%

map_df(operate(rowNum){

dataRow <- trainData[rowNum, ]

dataRow$knowledge[[1]] %>%

mutate(

activityName = dataRow$activityName,

observationId = dataRow$observationId,

time = 1:n() )

}) %>%

collect(studying, worth, -time, -activityName, -observationId) %>%

separate(studying, into = c("sort", "course"), sep = "_") %>%

mutate(sort = ifelse(sort == "a", "acceleration", "gyro"))Now we now have an unpacked set of our observations, let’s visualize them!

unpackedObs %>%

ggplot(aes(x = time, y = worth, colour = course)) +

geom_line(alpha = 0.2) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE, alpha = 0.7, dimension = 0.5) +

facet_grid(sort ~ activityName, scales = "free_y") +

theme_minimal() +

theme( axis.textual content.x = element_blank() )

So no less than within the accelerometer knowledge patterns positively emerge. One would think about that the mannequin might have bother with the variations between LIE_TO_SIT and LIE_TO_STAND as they’ve an identical profile on common. The identical goes for SIT_TO_STAND and STAND_TO_SIT.

Preprocessing

Earlier than we will prepare the neural community, we have to take a few steps to preprocess the information.

Padding observations

First we are going to resolve what size to pad (and truncate) our sequences to by discovering what the 98th percentile size is. By not utilizing the very longest statement size it will assist us keep away from extra-long outlier recordings messing up the padding.

padSize <- trainData$knowledge %>%

map_int(nrow) %>%

quantile(p = 0.98) %>%

ceiling()

padSize

98%

334 Now we merely must convert our checklist of observations to matrices, then use the tremendous useful pad_sequences() operate in Keras to pad all observations and switch them right into a 3D tensor for us.

convertToTensor <- . %>%

map(as.matrix) %>%

pad_sequences(maxlen = padSize)

trainObs <- trainData$knowledge %>% convertToTensor()

testObs <- testData$knowledge %>% convertToTensor()

dim(trainObs)

[1] 286 334 6Fantastic, we now have our knowledge in a pleasant neural-network-friendly format of a 3D tensor with dimensions (<num obs>, <sequence size>, <channels>).

One-hot encoding

There’s one last item we have to do earlier than we will prepare our mannequin, and that’s flip our statement lessons from integers into one-hot, or dummy encoded, vectors. Fortunately, once more Keras has provided us with a really useful operate to just do this.

oneHotClasses <- . %>%

{. - 7} %>% # convey integers right down to 0-6 from 7-12

to_categorical() # One-hot encode

trainY <- trainData$exercise %>% oneHotClasses()

testY <- testData$exercise %>% oneHotClasses()Modeling

Structure

Since we now have temporally dense time-series knowledge we are going to make use of 1D convolutional layers. With temporally-dense knowledge, an RNN has to study very lengthy dependencies so as to choose up on patterns, CNNs can merely stack a couple of convolutional layers to construct sample representations of considerable size. Since we’re additionally merely on the lookout for a single classification of exercise for every statement, we will simply use pooling to ‘summarize’ the CNNs view of the information right into a dense layer.

Along with stacking two layer_conv_1d() layers, we are going to use batch norm and dropout (the spatial variant(Tompson et al. 2014) on the convolutional layers and normal on the dense) to regularize the community.

input_shape <- dim(trainObs)[-1]

num_classes <- dim(trainY)[2]

filters <- 24 # variety of convolutional filters to study

kernel_size <- 8 # what number of time-steps every conv layer sees.

dense_size <- 48 # dimension of our penultimate dense layer.

# Initialize mannequin

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential()

mannequin %>%

layer_conv_1d(

filters = filters,

kernel_size = kernel_size,

input_shape = input_shape,

padding = "legitimate",

activation = "relu"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_spatial_dropout_1d(0.15) %>%

layer_conv_1d(

filters = filters/2,

kernel_size = kernel_size,

activation = "relu",

) %>%

# Apply common pooling:

layer_global_average_pooling_1d() %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_dense(

dense_size,

activation = "relu"

) %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_dropout(0.25) %>%

layer_dense(

num_classes,

activation = "softmax",

identify = "dense_output"

)

abstract(mannequin)

______________________________________________________________________

Layer (sort) Output Form Param #

======================================================================

conv1d_1 (Conv1D) (None, 327, 24) 1176

______________________________________________________________________

batch_normalization_1 (BatchNo (None, 327, 24) 96

______________________________________________________________________

spatial_dropout1d_1 (SpatialDr (None, 327, 24) 0

______________________________________________________________________

conv1d_2 (Conv1D) (None, 320, 12) 2316

______________________________________________________________________

global_average_pooling1d_1 (Gl (None, 12) 0

______________________________________________________________________

batch_normalization_2 (BatchNo (None, 12) 48

______________________________________________________________________

dropout_1 (Dropout) (None, 12) 0

______________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 48) 624

______________________________________________________________________

batch_normalization_3 (BatchNo (None, 48) 192

______________________________________________________________________

dropout_2 (Dropout) (None, 48) 0

______________________________________________________________________

dense_output (Dense) (None, 6) 294

======================================================================

Whole params: 4,746

Trainable params: 4,578

Non-trainable params: 168

______________________________________________________________________Coaching

Now we will prepare the mannequin utilizing our take a look at and coaching knowledge. Be aware that we use callback_model_checkpoint() to make sure that we save solely one of the best variation of the mannequin (fascinating since sooner or later in coaching the mannequin might start to overfit or in any other case cease bettering).

# Compile mannequin

mannequin %>% compile(

loss = "categorical_crossentropy",

optimizer = "rmsprop",

metrics = "accuracy"

)

trainHistory <- mannequin %>%

match(

x = trainObs, y = trainY,

epochs = 350,

validation_data = checklist(testObs, testY),

callbacks = checklist(

callback_model_checkpoint("best_model.h5",

save_best_only = TRUE)

)

)

The mannequin is studying one thing! We get a decent 94.4% accuracy on the validation knowledge, not unhealthy with six attainable lessons to select from. Let’s look into the validation efficiency a bit deeper to see the place the mannequin is messing up.

Analysis

Now that we now have a educated mannequin let’s examine the errors that it made on our testing knowledge. We are able to load one of the best mannequin from coaching based mostly upon validation accuracy after which take a look at every statement, what the mannequin predicted, how excessive a chance it assigned, and the true exercise label.

# dataframe to get labels onto one-hot encoded prediction columns

oneHotToLabel <- activityLabels %>%

mutate(quantity = quantity - 7) %>%

filter(quantity >= 0) %>%

mutate(class = paste0("V",quantity + 1)) %>%

choose(-number)

# Load our greatest mannequin checkpoint

bestModel <- load_model_hdf5("best_model.h5")

tidyPredictionProbs <- bestModel %>%

predict(testObs) %>%

as_data_frame() %>%

mutate(obs = 1:n()) %>%

collect(class, prob, -obs) %>%

right_join(oneHotToLabel, by = "class")

predictionPerformance <- tidyPredictionProbs %>%

group_by(obs) %>%

summarise(

highestProb = max(prob),

predicted = label[prob == highestProb]

) %>%

mutate(

reality = testData$activityName,

appropriate = reality == predicted

)

predictionPerformance %>% paged_table()First, let’s take a look at how ‘assured’ the mannequin was by if the prediction was appropriate or not.

predictionPerformance %>%

mutate(end result = ifelse(appropriate, 'Appropriate', 'Incorrect')) %>%

ggplot(aes(highestProb)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.01) +

geom_rug(alpha = 0.5) +

facet_grid(end result~.) +

ggtitle("Possibilities related to prediction by correctness")

Reassuringly it appears the mannequin was, on common, much less assured about its classifications for the inaccurate outcomes than the proper ones. (Though, the pattern dimension is simply too small to say something definitively.)

Let’s see what actions the mannequin had the toughest time with utilizing a confusion matrix.

predictionPerformance %>%

group_by(reality, predicted) %>%

summarise(depend = n()) %>%

mutate(good = reality == predicted) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = reality, y = predicted)) +

geom_point(aes(dimension = depend, colour = good)) +

geom_text(aes(label = depend),

hjust = 0, vjust = 0,

nudge_x = 0.1, nudge_y = 0.1) +

guides(colour = FALSE, dimension = FALSE) +

theme_minimal()

We see that, because the preliminary visualization prompt, the mannequin had a little bit of bother with distinguishing between LIE_TO_SIT and LIE_TO_STAND lessons, together with the SIT_TO_LIE and STAND_TO_LIE, which even have related visible profiles.

Future instructions

The obvious future course to take this evaluation could be to try to make the mannequin extra basic by working with extra of the provided exercise sorts. One other attention-grabbing course could be to not separate the recordings into distinct ‘observations’ however as a substitute maintain them as one streaming set of information, very similar to an actual world deployment of a mannequin would work, and see how effectively a mannequin might classify streaming knowledge and detect modifications in exercise.

Gal, Yarin, and Zoubin Ghahramani. 2016. “Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Mannequin Uncertainty in Deep Studying.” In Worldwide Convention on Machine Studying, 1050–9.

Graves, Alex. 2012. “Supervised Sequence Labelling.” In Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks, 5–13. Springer.

Kononenko, Igor. 1989. “Bayesian Neural Networks.” Organic Cybernetics 61 (5). Springer: 361–70.

LeCun, Yann, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. 2015. “Deep Studying.” Nature 521 (7553). Nature Publishing Group: 436.

Reyes-Ortiz, Jorge-L, Luca Oneto, Albert Samà, Xavier Parra, and Davide Anguita. 2016. “Transition-Conscious Human Exercise Recognition Utilizing Smartphones.” Neurocomputing 171. Elsevier: 754–67.

Tompson, Jonathan, Ross Goroshin, Arjun Jain, Yann LeCun, and Christoph Bregler. 2014. “Environment friendly Object Localization Utilizing Convolutional Networks.” CoRR abs/1411.4280. http://arxiv.org/abs/1411.4280.