About two weeks in the past, we launched TensorFlow Likelihood (TFP), exhibiting the best way to create and pattern from distributions and put them to make use of in a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) that learns its prior. At this time, we transfer on to a unique specimen within the VAE mannequin zoo: the Vector Quantised Variational Autoencoder (VQ-VAE) described in Neural Discrete Illustration Studying (Oord, Vinyals, and Kavukcuoglu 2017). This mannequin differs from most VAEs in that its approximate posterior will not be steady, however discrete – therefore the “quantised” within the article’s title. We’ll shortly have a look at what this implies, after which dive immediately into the code, combining Keras layers, keen execution, and TFP.

Many phenomena are greatest considered, and modeled, as discrete. This holds for phonemes and lexemes in language, higher-level buildings in photos (suppose objects as an alternative of pixels),and duties that necessitate reasoning and planning.

The latent code utilized in most VAEs, nevertheless, is steady – often it’s a multivariate Gaussian. Steady-space VAEs have been discovered very profitable in reconstructing their enter, however usually they endure from one thing known as posterior collapse: The decoder is so highly effective that it could create reasonable output given simply any enter. This implies there isn’t a incentive to be taught an expressive latent area.

In VQ-VAE, nevertheless, every enter pattern will get mapped deterministically to one in every of a set of embedding vectors. Collectively, these embedding vectors represent the prior for the latent area.

As such, an embedding vector accommodates much more info than a imply and a variance, and thus, is way more durable to disregard by the decoder.

The query then is: The place is that magical hat, for us to drag out significant embeddings?

From the above conceptual description, we now have two inquiries to reply. First, by what mechanism will we assign enter samples (that went by means of the encoder) to acceptable embedding vectors?

And second: How can we be taught embedding vectors that really are helpful representations – that when fed to a decoder, will lead to entities perceived as belonging to the identical species?

As regards task, a tensor emitted from the encoder is just mapped to its nearest neighbor in embedding area, utilizing Euclidean distance. The embedding vectors are then up to date utilizing exponential transferring averages. As we’ll see quickly, which means that they’re really not being discovered utilizing gradient descent – a characteristic value declaring as we don’t come throughout it day by day in deep studying.

Concretely, how then ought to the loss operate and coaching course of look? This may in all probability best be seen in code.

The whole code for this instance, together with utilities for mannequin saving and picture visualization, is accessible on github as a part of the Keras examples. Order of presentation right here might differ from precise execution order for expository functions, so please to really run the code take into account making use of the instance on github.

As in all our prior posts on VAEs, we use keen execution, which presupposes the TensorFlow implementation of Keras.

As in our earlier publish on doing VAE with TFP, we’ll use Kuzushiji-MNIST(Clanuwat et al. 2018) as enter.

Now could be the time to take a look at what we ended up producing that point and place your wager: How will that examine towards the discrete latent area of VQ-VAE?

np <- import("numpy")

kuzushiji <- np$load("kmnist-train-imgs.npz")

kuzushiji <- kuzushiji$get("arr_0")

train_images <- kuzushiji %>%

k_expand_dims() %>%

k_cast(dtype = "float32")

train_images <- train_images %>% `/`(255)

buffer_size <- 60000

batch_size <- 64

num_examples_to_generate <- batch_size

batches_per_epoch <- buffer_size / batch_size

train_dataset <- tensor_slices_dataset(train_images) %>%

dataset_shuffle(buffer_size) %>%

dataset_batch(batch_size, drop_remainder = TRUE)Hyperparameters

Along with the “standard” hyperparameters we’ve got in deep studying, the VQ-VAE infrastructure introduces just a few model-specific ones. Initially, the embedding area is of dimensionality variety of embedding vectors occasions embedding vector measurement:

# variety of embedding vectors

num_codes <- 64L

# dimensionality of the embedding vectors

code_size <- 16LThe latent area in our instance will probably be of measurement one, that’s, we’ve got a single embedding vector representing the latent code for every enter pattern. This will probably be high quality for our dataset, nevertheless it must be famous that van den Oord et al. used far higher-dimensional latent areas on e.g. ImageNet and Cifar-10.

Encoder mannequin

The encoder makes use of convolutional layers to extract picture options. Its output is a 3D tensor of form batchsize * 1 * code_size.

activation <- "elu"

# modularizing the code just a bit bit

default_conv <- set_defaults(layer_conv_2d, checklist(padding = "identical", activation = activation))base_depth <- 32

encoder_model <- operate(title = NULL,

code_size) {

keras_model_custom(title = title, operate(self) {

self$conv1 <- default_conv(filters = base_depth, kernel_size = 5)

self$conv2 <- default_conv(filters = base_depth, kernel_size = 5, strides = 2)

self$conv3 <- default_conv(filters = 2 * base_depth, kernel_size = 5)

self$conv4 <- default_conv(filters = 2 * base_depth, kernel_size = 5, strides = 2)

self$conv5 <- default_conv(filters = 4 * latent_size, kernel_size = 7, padding = "legitimate")

self$flatten <- layer_flatten()

self$dense <- layer_dense(models = latent_size * code_size)

self$reshape <- layer_reshape(target_shape = c(latent_size, code_size))

operate (x, masks = NULL) {

x %>%

# output form: 7 28 28 32

self$conv1() %>%

# output form: 7 14 14 32

self$conv2() %>%

# output form: 7 14 14 64

self$conv3() %>%

# output form: 7 7 7 64

self$conv4() %>%

# output form: 7 1 1 4

self$conv5() %>%

# output form: 7 4

self$flatten() %>%

# output form: 7 16

self$dense() %>%

# output form: 7 1 16

self$reshape()

}

})

}As at all times, let’s make use of the truth that we’re utilizing keen execution, and see just a few instance outputs.

iter <- make_iterator_one_shot(train_dataset)

batch <- iterator_get_next(iter)

encoder <- encoder_model(code_size = code_size)

encoded <- encoder(batch)

encodedtf.Tensor(

[[[ 0.00516277 -0.00746826 0.0268365 ... -0.012577 -0.07752544

-0.02947626]]

...

[[-0.04757921 -0.07282603 -0.06814402 ... -0.10861694 -0.01237121

0.11455103]]], form=(64, 1, 16), dtype=float32)Now, every of those 16d vectors must be mapped to the embedding vector it’s closest to. This mapping is taken care of by one other mannequin: vector_quantizer.

Vector quantizer mannequin

That is how we are going to instantiate the vector quantizer:

vector_quantizer <- vector_quantizer_model(num_codes = num_codes, code_size = code_size)This mannequin serves two functions: First, it acts as a retailer for the embedding vectors. Second, it matches encoder output to accessible embeddings.

Right here, the present state of embeddings is saved in codebook. ema_means and ema_count are for bookkeeping functions solely (notice how they’re set to be non-trainable). We’ll see them in use shortly.

vector_quantizer_model <- operate(title = NULL, num_codes, code_size) {

keras_model_custom(title = title, operate(self) {

self$num_codes <- num_codes

self$code_size <- code_size

self$codebook <- tf$get_variable(

"codebook",

form = c(num_codes, code_size),

dtype = tf$float32

)

self$ema_count <- tf$get_variable(

title = "ema_count", form = c(num_codes),

initializer = tf$constant_initializer(0),

trainable = FALSE

)

self$ema_means = tf$get_variable(

title = "ema_means",

initializer = self$codebook$initialized_value(),

trainable = FALSE

)

operate (x, masks = NULL) {

# to be crammed in shortly ...

}

})

}Along with the precise embeddings, in its name methodology vector_quantizer holds the task logic.

First, we compute the Euclidean distance of every encoding to the vectors within the codebook (tf$norm).

We assign every encoding to the closest as by that distance embedding (tf$argmin) and one-hot-encode the assignments (tf$one_hot). Lastly, we isolate the corresponding vector by masking out all others and summing up what’s left over (multiplication adopted by tf$reduce_sum).

Relating to the axis argument used with many TensorFlow features, please consider that in distinction to their k_* siblings, uncooked TensorFlow (tf$*) features count on axis numbering to be 0-based. We even have so as to add the L’s after the numbers to evolve to TensorFlow’s datatype necessities.

vector_quantizer_model <- operate(title = NULL, num_codes, code_size) {

keras_model_custom(title = title, operate(self) {

# right here we've got the above occasion fields

operate (x, masks = NULL) {

# form: bs * 1 * num_codes

distances <- tf$norm(

tf$expand_dims(x, axis = 2L) -

tf$reshape(self$codebook,

c(1L, 1L, self$num_codes, self$code_size)),

axis = 3L

)

# bs * 1

assignments <- tf$argmin(distances, axis = 2L)

# bs * 1 * num_codes

one_hot_assignments <- tf$one_hot(assignments, depth = self$num_codes)

# bs * 1 * code_size

nearest_codebook_entries <- tf$reduce_sum(

tf$expand_dims(

one_hot_assignments, -1L) *

tf$reshape(self$codebook, c(1L, 1L, self$num_codes, self$code_size)),

axis = 2L

)

checklist(nearest_codebook_entries, one_hot_assignments)

}

})

}Now that we’ve seen how the codes are saved, let’s add performance for updating them.

As we mentioned above, they aren’t discovered through gradient descent. As a substitute, they’re exponential transferring averages, frequently up to date by no matter new “class member” they get assigned.

So here’s a operate update_ema that may care for this.

update_ema makes use of TensorFlow moving_averages to

- first, preserve monitor of the variety of at present assigned samples per code (

updated_ema_count), and - second, compute and assign the present exponential transferring common (

updated_ema_means).

moving_averages <- tf$python$coaching$moving_averages

# decay to make use of in computing exponential transferring common

decay <- 0.99

update_ema <- operate(

vector_quantizer,

one_hot_assignments,

codes,

decay) {

updated_ema_count <- moving_averages$assign_moving_average(

vector_quantizer$ema_count,

tf$reduce_sum(one_hot_assignments, axis = c(0L, 1L)),

decay,

zero_debias = FALSE

)

updated_ema_means <- moving_averages$assign_moving_average(

vector_quantizer$ema_means,

# selects all assigned values (masking out the others) and sums them up over the batch

# (will probably be divided by rely later, so we get a median)

tf$reduce_sum(

tf$expand_dims(codes, 2L) *

tf$expand_dims(one_hot_assignments, 3L), axis = c(0L, 1L)),

decay,

zero_debias = FALSE

)

updated_ema_count <- updated_ema_count + 1e-5

updated_ema_means <- updated_ema_means / tf$expand_dims(updated_ema_count, axis = -1L)

tf$assign(vector_quantizer$codebook, updated_ema_means)

}Earlier than we have a look at the coaching loop, let’s shortly full the scene including within the final actor, the decoder.

Decoder mannequin

The decoder is fairly commonplace, performing a collection of deconvolutions and eventually, returning a chance for every picture pixel.

default_deconv <- set_defaults(

layer_conv_2d_transpose,

checklist(padding = "identical", activation = activation)

)

decoder_model <- operate(title = NULL,

input_size,

output_shape) {

keras_model_custom(title = title, operate(self) {

self$reshape1 <- layer_reshape(target_shape = c(1, 1, input_size))

self$deconv1 <-

default_deconv(

filters = 2 * base_depth,

kernel_size = 7,

padding = "legitimate"

)

self$deconv2 <-

default_deconv(filters = 2 * base_depth, kernel_size = 5)

self$deconv3 <-

default_deconv(

filters = 2 * base_depth,

kernel_size = 5,

strides = 2

)

self$deconv4 <-

default_deconv(filters = base_depth, kernel_size = 5)

self$deconv5 <-

default_deconv(filters = base_depth,

kernel_size = 5,

strides = 2)

self$deconv6 <-

default_deconv(filters = base_depth, kernel_size = 5)

self$conv1 <-

default_conv(filters = output_shape[3],

kernel_size = 5,

activation = "linear")

operate (x, masks = NULL) {

x <- x %>%

# output form: 7 1 1 16

self$reshape1() %>%

# output form: 7 7 7 64

self$deconv1() %>%

# output form: 7 7 7 64

self$deconv2() %>%

# output form: 7 14 14 64

self$deconv3() %>%

# output form: 7 14 14 32

self$deconv4() %>%

# output form: 7 28 28 32

self$deconv5() %>%

# output form: 7 28 28 32

self$deconv6() %>%

# output form: 7 28 28 1

self$conv1()

tfd$Unbiased(tfd$Bernoulli(logits = x),

reinterpreted_batch_ndims = size(output_shape))

}

})

}

input_shape <- c(28, 28, 1)

decoder <- decoder_model(input_size = latent_size * code_size,

output_shape = input_shape)Now we’re prepared to coach. One factor we haven’t actually talked about but is the price operate: Given the variations in structure (in comparison with commonplace VAEs), will the losses nonetheless look as anticipated (the standard add-up of reconstruction loss and KL divergence)?

We’ll see that in a second.

Coaching loop

Right here’s the optimizer we’ll use. Losses will probably be calculated inline.

optimizer <- tf$practice$AdamOptimizer(learning_rate = learning_rate)The coaching loop, as standard, is a loop over epochs, the place every iteration is a loop over batches obtained from the dataset.

For every batch, we’ve got a ahead move, recorded by a gradientTape, primarily based on which we calculate the loss.

The tape will then decide the gradients of all trainable weights all through the mannequin, and the optimizer will use these gradients to replace the weights.

To date, all of this conforms to a scheme we’ve oftentimes seen earlier than. One level to notice although: On this identical loop, we additionally name update_ema to recalculate the transferring averages, as these usually are not operated on throughout backprop.

Right here is the important performance:

num_epochs <- 20

for (epoch in seq_len(num_epochs)) {

iter <- make_iterator_one_shot(train_dataset)

until_out_of_range({

x <- iterator_get_next(iter)

with(tf$GradientTape(persistent = TRUE) %as% tape, {

# do ahead move

# calculate losses

})

encoder_gradients <- tape$gradient(loss, encoder$variables)

decoder_gradients <- tape$gradient(loss, decoder$variables)

optimizer$apply_gradients(purrr::transpose(checklist(

encoder_gradients, encoder$variables

)),

global_step = tf$practice$get_or_create_global_step())

optimizer$apply_gradients(purrr::transpose(checklist(

decoder_gradients, decoder$variables

)),

global_step = tf$practice$get_or_create_global_step())

update_ema(vector_quantizer,

one_hot_assignments,

codes,

decay)

# periodically show some generated photos

# see code on github

# visualize_images("kuzushiji", epoch, reconstructed_images, random_images)

})

}Now, for the precise motion. Contained in the context of the gradient tape, we first decide which encoded enter pattern will get assigned to which embedding vector.

codes <- encoder(x)

c(nearest_codebook_entries, one_hot_assignments) %<-% vector_quantizer(codes)Now, for this task operation there isn’t a gradient. As a substitute what we will do is move the gradients from decoder enter straight by means of to encoder output.

Right here tf$stop_gradient exempts nearest_codebook_entries from the chain of gradients, so encoder and decoder are linked by codes:

codes_straight_through <- codes + tf$stop_gradient(nearest_codebook_entries - codes)

decoder_distribution <- decoder(codes_straight_through)In sum, backprop will care for the decoder’s in addition to the encoder’s weights, whereas the latent embeddings are up to date utilizing transferring averages, as we’ve seen already.

Now we’re able to sort out the losses. There are three parts:

- First, the reconstruction loss, which is simply the log chance of the particular enter below the distribution discovered by the decoder.

reconstruction_loss <- -tf$reduce_mean(decoder_distribution$log_prob(x))- Second, we’ve got the dedication loss, outlined because the imply squared deviation of the encoded enter samples from the closest neighbors they’ve been assigned to: We wish the community to “commit” to a concise set of latent codes!

commitment_loss <- tf$reduce_mean(tf$sq.(codes - tf$stop_gradient(nearest_codebook_entries)))- Lastly, we’ve got the standard KL diverge to a previous. As, a priori, all assignments are equally possible, this part of the loss is fixed and might oftentimes be disbursed of. We’re including it right here primarily for illustrative functions.

prior_dist <- tfd$Multinomial(

total_count = 1,

logits = tf$zeros(c(latent_size, num_codes))

)

prior_loss <- -tf$reduce_mean(

tf$reduce_sum(prior_dist$log_prob(one_hot_assignments), 1L)

)Summing up all three parts, we arrive on the general loss:

beta <- 0.25

loss <- reconstruction_loss + beta * commitment_loss + prior_lossEarlier than we have a look at the outcomes, let’s see what occurs inside gradientTape at a single look:

with(tf$GradientTape(persistent = TRUE) %as% tape, {

codes <- encoder(x)

c(nearest_codebook_entries, one_hot_assignments) %<-% vector_quantizer(codes)

codes_straight_through <- codes + tf$stop_gradient(nearest_codebook_entries - codes)

decoder_distribution <- decoder(codes_straight_through)

reconstruction_loss <- -tf$reduce_mean(decoder_distribution$log_prob(x))

commitment_loss <- tf$reduce_mean(tf$sq.(codes - tf$stop_gradient(nearest_codebook_entries)))

prior_dist <- tfd$Multinomial(

total_count = 1,

logits = tf$zeros(c(latent_size, num_codes))

)

prior_loss <- -tf$reduce_mean(tf$reduce_sum(prior_dist$log_prob(one_hot_assignments), 1L))

loss <- reconstruction_loss + beta * commitment_loss + prior_loss

})Outcomes

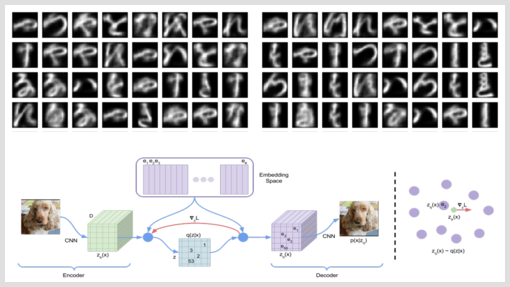

And right here we go. This time, we will’t have the second “morphing view” one typically likes to show with VAEs (there simply isn’t any second latent area). As a substitute, the 2 photos beneath are (1) letters generated from random enter and (2) reconstructed precise letters, every saved after coaching for 9 epochs.

Two issues soar to the attention: First, the generated letters are considerably sharper than their continuous-prior counterparts (from the earlier publish). And second, would you’ve got been in a position to inform the random picture from the reconstruction picture?

At this level, we’ve hopefully satisfied you of the facility and effectiveness of this discrete-latents method.

Nonetheless, you may secretly have hoped we’d apply this to extra complicated information, comparable to the weather of speech we talked about within the introduction, or higher-resolution photos as present in ImageNet.

The reality is that there’s a steady tradeoff between the variety of new and thrilling methods we will present, and the time we will spend on iterations to efficiently apply these methods to complicated datasets. In the long run it’s you, our readers, who will put these methods to significant use on related, actual world information.