The well-known Pantheon in Rome boasts the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome—an architectural marvel that has endured for millennia, due to the unimaginable sturdiness of historical Roman concrete. For many years, scientists have been making an attempt to find out exactly what makes the fabric so sturdy. A brand new evaluation of samples taken from the concrete partitions of the Privernum archaeological web site close to Rome has yielded insights into these elusive manufacturing secrets and techniques. It appears the Romans employed “sizzling mixing” with quicklime, amongst different methods, that gave the fabric self-healing performance, in response to a new paper revealed within the journal Science Advances.

As we have reported beforehand, like at present’s Portland cement (a primary ingredient of recent concrete), historical Roman concrete was principally a mixture of a semi-liquid mortar and mixture. Portland cement is often made by heating limestone and clay (in addition to sandstone, ash, chalk, and iron) in a kiln. The ensuing clinker is then floor right into a effective powder, with only a contact of added gypsum—the higher to realize a clean, flat floor. However the mixture used to make Roman concrete was made up of fist-sized items of stone or bricks.

In his treatise De architectura (circa 30 CE), the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote about learn how to construct concrete partitions for funerary buildings that would endure for a very long time with out falling into ruins. He advisable the partitions be no less than two toes thick, product of both “squared crimson stone or of brick or lava laid in programs.” The brick or volcanic rock mixture ought to be certain with mortar composed of hydrated lime and porous fragments of glass and crystals from volcanic eruptions (generally known as volcanic tephra).

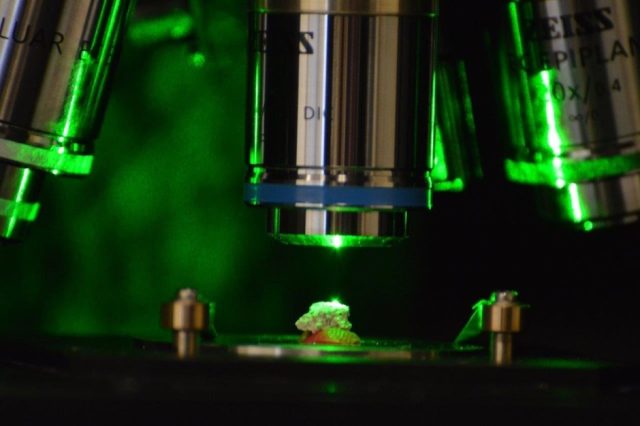

Admir Masic, an surroundings engineer at MIT, has studied historical Roman concrete for a number of years. As an illustration, in 2019, Masic and two colleagues (MIT’s Janille Maragh and Harvard’s James Weaver) pioneered a brand new set of instruments for analyzing Roman concrete samples from Privernum at a number of size scales—notably Raman spectroscopy for chemical profiling and multi-detector power dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for section mapping of the fabric.

Masic was additionally a co-author of a 2021 research analyzing samples of the traditional concrete used to construct a 2,000-year-old mausoleum alongside the Appian Means in Rome generally known as the Tomb of Caecilia Metella, a noblewoman who lived within the first century CE. It is broadly thought-about one of many best-preserved monuments on the Appian Means. They used the Superior Mild Supply to establish the various totally different minerals contained within the samples and their orientation, in addition to scanning electron microscopy.

They found that the tomb’s mortar was much like the partitions of the Markets of Trajan: volcanic tephra from the Pozzolane Rosse pyroclastic circulation, binding collectively giant chunks of brick and lava mixture. Nonetheless, the tephra used within the tomb’s mortar contained way more potassium-rich leucite. The potassium within the mortar dissolved in flip and successfully reconfigured the binding section. Some components remained intact after greater than 2,000 years, whereas different areas appeared wispier and confirmed some indicators of splitting. In reality, the construction considerably resembled nanocrystals. So the interfacial zones always evolve via long-term transforming, reinforcing these interfacial zones.

For this newest research, Masic needed to take a better take a look at unusual white mineral chunks generally known as “lime clasts,” which others had largely dismissed as ensuing from subpar uncooked supplies or poor mixing. “The concept the presence of those lime clasts was merely attributed to low high quality management all the time bothered me,” mentioned Masic. “If the Romans put a lot effort into making an impressive building materials, following all the detailed recipes that had been optimized over the course of many centuries, why would they put so little effort into guaranteeing the manufacturing of a well-mixed ultimate product? There must be extra to this story.”

It was believed that the Romans mixed water with lime to make a extremely chemically reactive paste (slaking), however this would not clarify the lime clasts. Masic thought they may have used the much more reactive quicklime (probably together with slaked lime), and his suspicion was born out by the lab’s evaluation with chemical mapping and multi-scale imaging instruments. The clasts have been totally different types of calcium carbonate, and spectroscopic evaluation confirmed these clasts had fashioned at extraordinarily excessive temperatures—aka sizzling mixing.

“The advantages of sizzling mixing are twofold,” Masic mentioned. “First, when the general concrete is heated to excessive temperatures, it permits chemistries that aren’t attainable in case you solely used slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that might not in any other case type. Second, this elevated temperature considerably reduces curing and setting instances since all of the reactions are accelerated, permitting for a lot quicker building.”

It additionally appears to impart self-healing capabilities. Per Masic, when cracks start to type within the concrete, they’re extra more likely to transfer via the lime clasts. The clasts can then react with water, producing an answer saturated with calcium. That resolution can both recrystallize as calcium carbonate to fill the cracks or react with the pozzolanic parts to strengthen the composite materials.

Masic et al. discovered proof of calcite-filled cracks in different samples of Roman concrete, supporting their speculation. In addition they created concrete samples within the lab with a sizzling mixing course of, utilizing historical and trendy recipes, then intentionally cracked the samples and ran water via them. They discovered that the cracks within the samples made with hot-mixed quicklime healed fully inside two weeks, whereas the cracks by no means healed within the samples with out quicklime.

DOI: Science Advances, 2022. 10.1126/sciadv.add1602 (About DOIs).