About six months in the past, we confirmed easy methods to create a customized wrapper to acquire uncertainty estimates from a Keras community. Immediately we current a much less laborious, as properly faster-running approach utilizing tfprobability, the R wrapper to TensorFlow Chance. Like most posts on this weblog, this one gained’t be brief, so let’s shortly state what you possibly can anticipate in return of studying time.

What to anticipate from this put up

Ranging from what not to anticipate: There gained’t be a recipe that tells you the way precisely to set all parameters concerned with a view to report the “proper” uncertainty measures. However then, what are the “proper” uncertainty measures? Until you occur to work with a way that has no (hyper-)parameters to tweak, there’ll at all times be questions on easy methods to report uncertainty.

What you can anticipate, although, is an introduction to acquiring uncertainty estimates for Keras networks, in addition to an empirical report of how tweaking (hyper-)parameters could have an effect on the outcomes. As within the aforementioned put up, we carry out our exams on each a simulated and an actual dataset, the Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set. On the finish, instead of strict guidelines, it is best to have acquired some instinct that may switch to different real-world datasets.

Did you discover our speaking about Keras networks above? Certainly this put up has an extra objective: To this point, we haven’t actually mentioned but how tfprobability goes along with keras. Now we lastly do (in brief: they work collectively seemlessly).

Lastly, the notions of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty, which can have stayed a bit summary within the prior put up, ought to get rather more concrete right here.

Aleatoric vs. epistemic uncertainty

Reminiscent someway of the basic decomposition of generalization error into bias and variance, splitting uncertainty into its epistemic and aleatoric constituents separates an irreducible from a reducible half.

The reducible half pertains to imperfection within the mannequin: In principle, if our mannequin have been good, epistemic uncertainty would vanish. Put in a different way, if the coaching knowledge have been limitless – or in the event that they comprised the entire inhabitants – we might simply add capability to the mannequin till we’ve obtained an ideal match.

In distinction, usually there’s variation in our measurements. There could also be one true course of that determines my resting coronary heart fee; nonetheless, precise measurements will range over time. There’s nothing to be completed about this: That is the aleatoric half that simply stays, to be factored into our expectations.

Now studying this, you is likely to be considering: “Wouldn’t a mannequin that really have been good seize these pseudo-random fluctuations?”. We’ll depart that phisosophical query be; as a substitute, we’ll attempt to illustrate the usefulness of this distinction by instance, in a sensible approach. In a nutshell, viewing a mannequin’s aleatoric uncertainty output ought to warning us to consider acceptable deviations when making our predictions, whereas inspecting epistemic uncertainty ought to assist us re-think the appropriateness of the chosen mannequin.

Now let’s dive in and see how we could accomplish our objective with tfprobability. We begin with the simulated dataset.

Uncertainty estimates on simulated knowledge

Dataset

We re-use the dataset from the Google TensorFlow Chance group’s weblog put up on the identical topic , with one exception: We prolong the vary of the impartial variable a bit on the destructive facet, to higher display the totally different strategies’ behaviors.

Right here is the data-generating course of. We additionally get library loading out of the best way. Just like the previous posts on tfprobability, this one too options lately added performance, so please use the event variations of tensorflow and tfprobability in addition to keras. Name install_tensorflow(model = "nightly") to acquire a present nightly construct of TensorFlow and TensorFlow Chance:

# make certain we use the event variations of tensorflow, tfprobability and keras

devtools::install_github("rstudio/tensorflow")

devtools::install_github("rstudio/tfprobability")

devtools::install_github("rstudio/keras")

# and that we use a nightly construct of TensorFlow and TensorFlow Chance

tensorflow::install_tensorflow(model = "nightly")

library(tensorflow)

library(tfprobability)

library(keras)

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

library(ggplot2)

# make certain this code is suitable with TensorFlow 2.0

tf$compat$v1$enable_v2_behavior()

# generate the information

x_min <- -40

x_max <- 60

n <- 150

w0 <- 0.125

b0 <- 5

normalize <- operate(x) (x - x_min) / (x_max - x_min)

# coaching knowledge; predictor

x <- x_min + (x_max - x_min) * runif(n) %>% as.matrix()

# coaching knowledge; goal

eps <- rnorm(n) * (3 * (0.25 + (normalize(x)) ^ 2))

y <- (w0 * x * (1 + sin(x)) + b0) + eps

# take a look at knowledge (predictor)

x_test <- seq(x_min, x_max, size.out = n) %>% as.matrix()How does the information look?

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = x, y = y), aes(x, y)) + geom_point()

Determine 1: Simulated knowledge

The duty right here is single-predictor regression, which in precept we are able to obtain use Keras dense layers.

Let’s see easy methods to improve this by indicating uncertainty, ranging from the aleatoric sort.

Aleatoric uncertainty

Aleatoric uncertainty, by definition, shouldn’t be an announcement in regards to the mannequin. So why not have the mannequin study the uncertainty inherent within the knowledge?

That is precisely how aleatoric uncertainty is operationalized on this strategy. As an alternative of a single output per enter – the expected imply of the regression – right here now we have two outputs: one for the imply, and one for the usual deviation.

How will we use these? Till shortly, we might have needed to roll our personal logic. Now with tfprobability, we make the community output not tensors, however distributions – put in a different way, we make the final layer a distribution layer.

Distribution layers are Keras layers, however contributed by tfprobability. The superior factor is that we are able to prepare them with simply tensors as targets, as typical: No must compute possibilities ourselves.

A number of specialised distribution layers exist, corresponding to layer_kl_divergence_add_loss, layer_independent_bernoulli, or layer_mixture_same_family, however probably the most basic is layer_distribution_lambda. layer_distribution_lambda takes as inputs the previous layer and outputs a distribution. So as to have the ability to do that, we have to inform it easy methods to make use of the previous layer’s activations.

In our case, sooner or later we are going to need to have a dense layer with two models.

... %>% layer_dense(models = 2, activation = "linear") %>%Then layer_distribution_lambda will use the primary unit because the imply of a standard distribution, and the second as its commonplace deviation.

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x[, 1, drop = FALSE],

scale = 1e-3 + tf$math$softplus(x[, 2, drop = FALSE])

)

)Right here is the entire mannequin we use. We insert an extra dense layer in entrance, with a relu activation, to offer the mannequin a bit extra freedom and capability. We talk about this, in addition to that scale = ... foo, as quickly as we’ve completed our walkthrough of mannequin coaching.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense(models = 8, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(models = 2, activation = "linear") %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x[, 1, drop = FALSE],

# ignore on first learn, we'll come again to this

# scale = 1e-3 + 0.05 * tf$math$softplus(x[, 2, drop = FALSE])

scale = 1e-3 + tf$math$softplus(x[, 2, drop = FALSE])

)

)For a mannequin that outputs a distribution, the loss is the destructive log probability given the goal knowledge.

negloglik <- operate(y, mannequin) - (mannequin %>% tfd_log_prob(y))We will now compile and match the mannequin.

We now name the mannequin on the take a look at knowledge to acquire the predictions. The predictions now truly are distributions, and now we have 150 of them, one for every datapoint:

yhat <- mannequin(tf$fixed(x_test))tfp.distributions.Regular("sequential/distribution_lambda/Regular/",

batch_shape=[150, 1], event_shape=[], dtype=float32)To acquire the means and commonplace deviations – the latter being that measure of aleatoric uncertainty we’re desirous about – we simply name tfd_mean and tfd_stddev on these distributions.

That may give us the expected imply, in addition to the expected variance, per datapoint.

Let’s visualize this. Listed here are the precise take a look at knowledge factors, the expected means, in addition to confidence bands indicating the imply estimate plus/minus two commonplace deviations.

ggplot(knowledge.body(

x = x,

y = y,

imply = as.numeric(imply),

sd = as.numeric(sd)

),

aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(x = x_test, y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_ribbon(aes(

x = x_test,

ymin = imply - 2 * sd,

ymax = imply + 2 * sd

),

alpha = 0.2,

fill = "gray")

Determine 2: Aleatoric uncertainty on simulated knowledge, utilizing relu activation within the first dense layer.

This seems to be fairly cheap. What if we had used linear activation within the first layer? That means, what if the mannequin had seemed like this:

This time, the mannequin doesn’t seize the “type” of the information that properly, as we’ve disallowed any nonlinearities.

Determine 3: Aleatoric uncertainty on simulated knowledge, utilizing linear activation within the first dense layer.

Utilizing linear activations solely, we additionally must do extra experimenting with the scale = ... line to get the end result look “proper”. With relu, alternatively, outcomes are fairly strong to adjustments in how scale is computed. Which activation can we select? If our objective is to adequately mannequin variation within the knowledge, we are able to simply select relu – and depart assessing uncertainty within the mannequin to a unique approach (the epistemic uncertainty that’s up subsequent).

General, it looks like aleatoric uncertainty is the simple half. We would like the community to study the variation inherent within the knowledge, which it does. What can we acquire? As an alternative of acquiring simply level estimates, which on this instance would possibly prove fairly dangerous within the two fan-like areas of the information on the left and proper sides, we study in regards to the unfold as properly. We’ll thus be appropriately cautious relying on what enter vary we’re making predictions for.

Epistemic uncertainty

Now our focus is on the mannequin. Given a speficic mannequin (e.g., one from the linear household), what sort of knowledge does it say conforms to its expectations?

To reply this query, we make use of a variational-dense layer.

That is once more a Keras layer supplied by tfprobability. Internally, it really works by minimizing the proof decrease sure (ELBO), thus striving to seek out an approximative posterior that does two issues:

- match the precise knowledge properly (put in a different way: obtain excessive log probability), and

- keep near a prior (as measured by KL divergence).

As customers, we truly specify the type of the posterior in addition to that of the prior. Right here is how a previous might look.

prior_trainable <-

operate(kernel_size,

bias_size = 0,

dtype = NULL) {

n <- kernel_size + bias_size

keras_model_sequential() %>%

# we'll touch upon this quickly

# layer_variable(n, dtype = dtype, trainable = FALSE) %>%

layer_variable(n, dtype = dtype, trainable = TRUE) %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(t) {

tfd_independent(tfd_normal(loc = t, scale = 1),

reinterpreted_batch_ndims = 1)

})

}This prior is itself a Keras mannequin, containing a layer that wraps a variable and a layer_distribution_lambda, that sort of distribution-yielding layer we’ve simply encountered above. The variable layer may very well be fastened (non-trainable) or non-trainable, similar to a real prior or a previous learnt from the information in an empirical Bayes-like approach. The distribution layer outputs a standard distribution since we’re in a regression setting.

The posterior too is a Keras mannequin – undoubtedly trainable this time. It too outputs a standard distribution:

posterior_mean_field <-

operate(kernel_size,

bias_size = 0,

dtype = NULL) {

n <- kernel_size + bias_size

c <- log(expm1(1))

keras_model_sequential(listing(

layer_variable(form = 2 * n, dtype = dtype),

layer_distribution_lambda(

make_distribution_fn = operate(t) {

tfd_independent(tfd_normal(

loc = t[1:n],

scale = 1e-5 + tf$nn$softplus(c + t[(n + 1):(2 * n)])

), reinterpreted_batch_ndims = 1)

}

)

))

}Now that we’ve outlined each, we are able to arrange the mannequin’s layers. The primary one, a variational-dense layer, has a single unit. The following distribution layer then takes that unit’s output and makes use of it for the imply of a standard distribution – whereas the size of that Regular is fastened at 1:

You will have observed one argument to layer_dense_variational we haven’t mentioned but, kl_weight.

That is used to scale the contribution to the whole lack of the KL divergence, and usually ought to equal one over the variety of knowledge factors.

Coaching the mannequin is easy. As customers, we solely specify the destructive log probability a part of the loss; the KL divergence half is taken care of transparently by the framework.

Due to the stochasticity inherent in a variational-dense layer, every time we name this mannequin, we acquire totally different outcomes: totally different regular distributions, on this case.

To acquire the uncertainty estimates we’re in search of, we subsequently name the mannequin a bunch of instances – 100, say:

yhats <- purrr::map(1:100, operate(x) mannequin(tf$fixed(x_test)))We will now plot these 100 predictions – traces, on this case, as there are not any nonlinearities:

means <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_mean)) %>% abind::abind()

traces <- knowledge.body(cbind(x_test, means)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = worth,-X1)

imply <- apply(means, 1, imply)

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = x, y = y, imply = as.numeric(imply)), aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(x = x_test, y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_line(

knowledge = traces,

aes(x = X1, y = worth, shade = run),

alpha = 0.3,

measurement = 0.5

) +

theme(legend.place = "none")

Determine 4: Epistemic uncertainty on simulated knowledge, utilizing linear activation within the variational-dense layer.

What we see listed below are basically totally different fashions, in line with the assumptions constructed into the structure. What we’re not accounting for is the unfold within the knowledge. Can we do each? We will; however first let’s touch upon a number of selections that have been made and see how they have an effect on the outcomes.

To forestall this put up from rising to infinite measurement, we’ve kept away from performing a scientific experiment; please take what follows not as generalizable statements, however as tips that could issues it would be best to bear in mind in your personal ventures. Particularly, every (hyper-)parameter shouldn’t be an island; they might work together in unexpected methods.

After these phrases of warning, listed below are some issues we observed.

- One query you would possibly ask: Earlier than, within the aleatoric uncertainty setup, we added an extra dense layer to the mannequin, with

reluactivation. What if we did this right here?

Firstly, we’re not including any extra, non-variational layers with a view to preserve the setup “totally Bayesian” – we would like priors at each stage. As to utilizingreluinlayer_dense_variational, we did strive that, and the outcomes look fairly related:

Determine 5: Epistemic uncertainty on simulated knowledge, utilizing relu activation within the variational-dense layer.

Nevertheless, issues look fairly totally different if we drastically scale back coaching time… which brings us to the subsequent commentary.

- Not like within the aleatoric setup, the variety of coaching epochs matter quite a bit. If we prepare, quote unquote, too lengthy, the posterior estimates will get nearer and nearer to the posterior imply: we lose uncertainty. What occurs if we prepare “too brief” is much more notable. Listed here are the outcomes for the linear-activation in addition to the relu-activation instances:

Determine 6: Epistemic uncertainty on simulated knowledge if we prepare for 100 epochs solely. Left: linear activation. Proper: relu activation.

Curiously, each mannequin households look very totally different now, and whereas the linear-activation household seems to be extra cheap at first, it nonetheless considers an general destructive slope in line with the information.

So what number of epochs are “lengthy sufficient”? From commentary, we’d say {that a} working heuristic ought to most likely be primarily based on the speed of loss discount. However definitely, it’ll make sense to strive totally different numbers of epochs and test the impact on mannequin conduct. As an apart, monitoring estimates over coaching time could even yield essential insights into the assumptions constructed right into a mannequin (e.g., the impact of various activation features).

-

As essential because the variety of epochs educated, and related in impact, is the studying fee. If we exchange the training fee on this setup by

0.001, outcomes will look much like what we noticed above for theepochs = 100case. Once more, we are going to need to strive totally different studying charges and ensure we prepare the mannequin “to completion” in some cheap sense. -

To conclude this part, let’s shortly take a look at what occurs if we range two different parameters. What if the prior have been non-trainable (see the commented line above)? And what if we scaled the significance of the KL divergence (

kl_weightinlayer_dense_variational’s argument listing) in a different way, changingkl_weight = 1/nbykl_weight = 1(or equivalently, eradicating it)? Listed here are the respective outcomes for an otherwise-default setup. They don’t lend themselves to generalization – on totally different (e.g., greater!) datasets the outcomes will most definitely look totally different – however undoubtedly fascinating to watch.

Determine 7: Epistemic uncertainty on simulated knowledge. Left: kl_weight = 1. Proper: prior non-trainable.

Now let’s come again to the query: We’ve modeled unfold within the knowledge, we’ve peeked into the guts of the mannequin, – can we do each on the identical time?

We will, if we mix each approaches. We add an extra unit to the variational-dense layer and use this to study the variance: as soon as for every “sub-model” contained within the mannequin.

Combining each aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty

Reusing the prior and posterior from above, that is how the ultimate mannequin seems to be:

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense_variational(

models = 2,

make_posterior_fn = posterior_mean_field,

make_prior_fn = prior_trainable,

kl_weight = 1 / n

) %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x[, 1, drop = FALSE],

scale = 1e-3 + tf$math$softplus(0.01 * x[, 2, drop = FALSE])

)

)We prepare this mannequin similar to the epistemic-uncertainty just one. We then acquire a measure of uncertainty per predicted line. Or within the phrases we used above, we now have an ensemble of fashions every with its personal indication of unfold within the knowledge. Here’s a approach we might show this – every coloured line is the imply of a distribution, surrounded by a confidence band indicating +/- two commonplace deviations.

yhats <- purrr::map(1:100, operate(x) mannequin(tf$fixed(x_test)))

means <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_mean)) %>% abind::abind()

sds <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_stddev)) %>% abind::abind()

means_gathered <- knowledge.body(cbind(x_test, means)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = mean_val,-X1)

sds_gathered <- knowledge.body(cbind(x_test, sds)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = sd_val,-X1)

traces <-

means_gathered %>% inner_join(sds_gathered, by = c("X1", "run"))

imply <- apply(means, 1, imply)

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = x, y = y, imply = as.numeric(imply)), aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

theme(legend.place = "none") +

geom_line(aes(x = x_test, y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_line(

knowledge = traces,

aes(x = X1, y = mean_val, shade = run),

alpha = 0.6,

measurement = 0.5

) +

geom_ribbon(

knowledge = traces,

aes(

x = X1,

ymin = mean_val - 2 * sd_val,

ymax = mean_val + 2 * sd_val,

group = run

),

alpha = 0.05,

fill = "gray",

inherit.aes = FALSE

)

Determine 8: Displaying each epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty on the simulated dataset.

Good! This seems to be like one thing we might report.

As you may think, this mannequin, too, is delicate to how lengthy (assume: variety of epochs) or how briskly (assume: studying fee) we prepare it. And in comparison with the epistemic-uncertainty solely mannequin, there’s an extra option to be made right here: the scaling of the earlier layer’s activation – the 0.01 within the scale argument to tfd_normal:

scale = 1e-3 + tf$math$softplus(0.01 * x[, 2, drop = FALSE])Protecting all the things else fixed, right here we range that parameter between 0.01 and 0.05:

Determine 9: Epistemic plus aleatoric uncertainty on the simulated dataset: Various the size argument.

Evidently, that is one other parameter we needs to be ready to experiment with.

Now that we’ve launched all three kinds of presenting uncertainty – aleatoric solely, epistemic solely, or each – let’s see them on the aforementioned Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set. Please see our earlier put up on uncertainty for a fast characterization, in addition to visualization, of the dataset.

Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set

To maintain this put up at a digestible size, we’ll chorus from making an attempt as many alternate options as with the simulated knowledge and primarily stick with what labored properly there. This also needs to give us an concept of how properly these “defaults” generalize. We individually examine two situations: The one-predictor setup (utilizing every of the 4 obtainable predictors alone), and the entire one (utilizing all 4 predictors directly).

The dataset is loaded simply as within the earlier put up.

First we take a look at the single-predictor case, ranging from aleatoric uncertainty.

Single predictor: Aleatoric uncertainty

Right here is the “default” aleatoric mannequin once more. We additionally duplicate the plotting code right here for the reader’s comfort.

n <- nrow(X_train) # 7654

n_epochs <- 10 # we want fewer epochs as a result of the dataset is a lot greater

batch_size <- 100

learning_rate <- 0.01

# variable to suit - change to 2,3,4 to get the opposite predictors

i <- 1

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense(models = 16, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(models = 2, activation = "linear") %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x[, 1, drop = FALSE],

scale = tf$math$softplus(x[, 2, drop = FALSE])

)

)

negloglik <- operate(y, mannequin) - (mannequin %>% tfd_log_prob(y))

mannequin %>% compile(optimizer = optimizer_adam(lr = learning_rate), loss = negloglik)

hist <-

mannequin %>% match(

X_train[, i, drop = FALSE],

y_train,

validation_data = listing(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE], y_val),

epochs = n_epochs,

batch_size = batch_size

)

yhat <- mannequin(tf$fixed(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE]))

imply <- yhat %>% tfd_mean()

sd <- yhat %>% tfd_stddev()

ggplot(knowledge.body(

x = X_val[, i],

y = y_val,

imply = as.numeric(imply),

sd = as.numeric(sd)

),

aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(x = x, y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_ribbon(aes(

x = x,

ymin = imply - 2 * sd,

ymax = imply + 2 * sd

),

alpha = 0.4,

fill = "gray")How properly does this work?

Determine 10: Aleatoric uncertainty on the Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set; single predictors.

This seems to be fairly good we’d say! How about epistemic uncertainty?

Single predictor: Epistemic uncertainty

Right here’s the code:

posterior_mean_field <-

operate(kernel_size,

bias_size = 0,

dtype = NULL) {

n <- kernel_size + bias_size

c <- log(expm1(1))

keras_model_sequential(listing(

layer_variable(form = 2 * n, dtype = dtype),

layer_distribution_lambda(

make_distribution_fn = operate(t) {

tfd_independent(tfd_normal(

loc = t[1:n],

scale = 1e-5 + tf$nn$softplus(c + t[(n + 1):(2 * n)])

), reinterpreted_batch_ndims = 1)

}

)

))

}

prior_trainable <-

operate(kernel_size,

bias_size = 0,

dtype = NULL) {

n <- kernel_size + bias_size

keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_variable(n, dtype = dtype, trainable = TRUE) %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(t) {

tfd_independent(tfd_normal(loc = t, scale = 1),

reinterpreted_batch_ndims = 1)

})

}

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense_variational(

models = 1,

make_posterior_fn = posterior_mean_field,

make_prior_fn = prior_trainable,

kl_weight = 1 / n,

activation = "linear",

) %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x, scale = 1))

negloglik <- operate(y, mannequin) - (mannequin %>% tfd_log_prob(y))

mannequin %>% compile(optimizer = optimizer_adam(lr = learning_rate), loss = negloglik)

hist <-

mannequin %>% match(

X_train[, i, drop = FALSE],

y_train,

validation_data = listing(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE], y_val),

epochs = n_epochs,

batch_size = batch_size

)

yhats <- purrr::map(1:100, operate(x)

yhat <- mannequin(tf$fixed(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE])))

means <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_mean)) %>% abind::abind()

traces <- knowledge.body(cbind(X_val[, i], means)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = worth,-X1)

imply <- apply(means, 1, imply)

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = X_val[, i], y = y_val, imply = as.numeric(imply)), aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

geom_line(aes(x = X_val[, i], y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_line(

knowledge = traces,

aes(x = X1, y = worth, shade = run),

alpha = 0.3,

measurement = 0.5

) +

theme(legend.place = "none")And that is the end result.

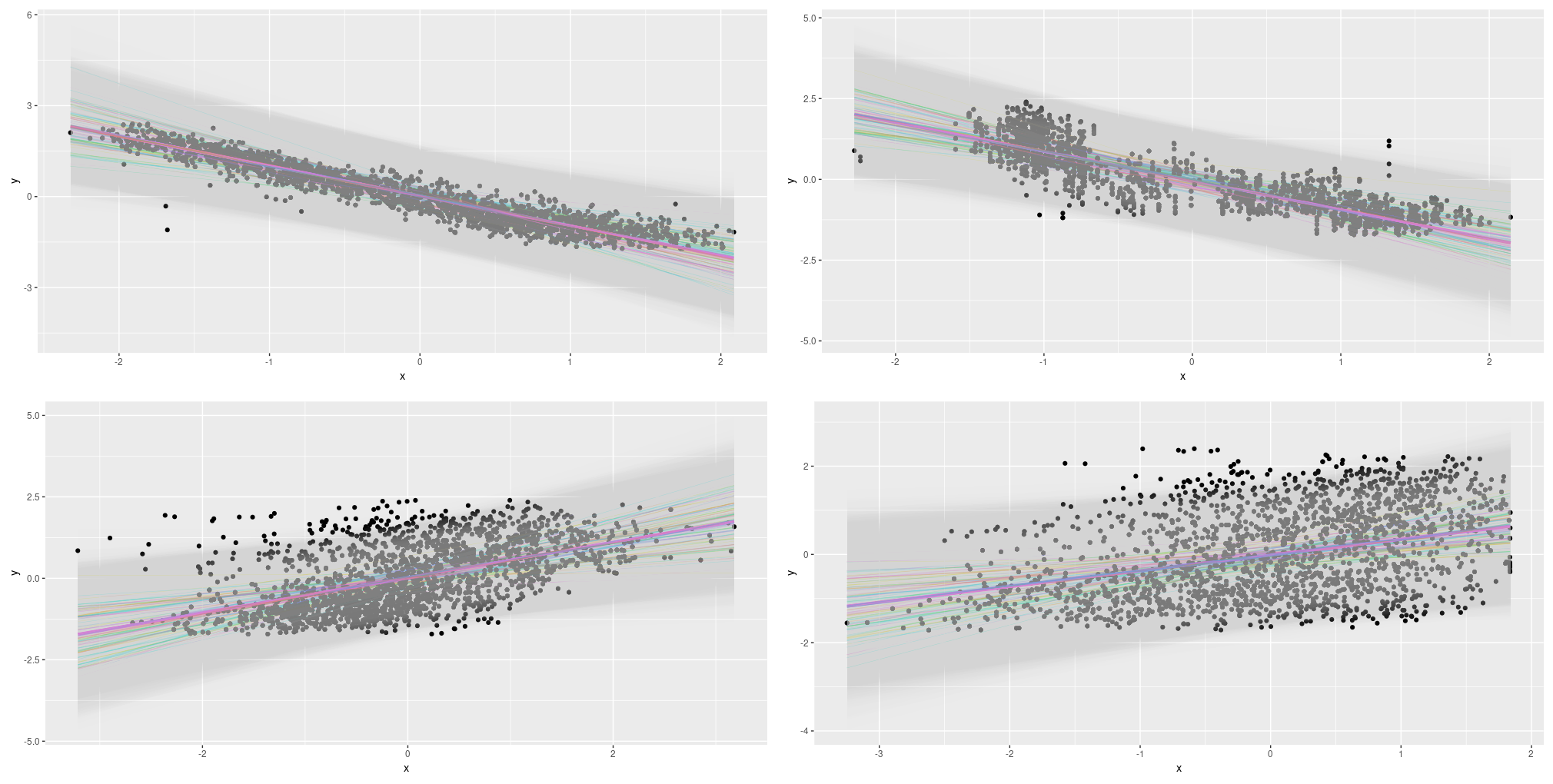

Determine 11: Epistemic uncertainty on the Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set; single predictors.

As with the simulated knowledge, the linear fashions appears to “do the suitable factor”. And right here too, we expect we are going to need to increase this with the unfold within the knowledge: Thus, on to approach three.

Single predictor: Combining each sorts

Right here we go. Once more, posterior_mean_field and prior_trainable look similar to within the epistemic-only case.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense_variational(

models = 2,

make_posterior_fn = posterior_mean_field,

make_prior_fn = prior_trainable,

kl_weight = 1 / n,

activation = "linear"

) %>%

layer_distribution_lambda(operate(x)

tfd_normal(loc = x[, 1, drop = FALSE],

scale = 1e-3 + tf$math$softplus(0.01 * x[, 2, drop = FALSE])))

negloglik <- operate(y, mannequin)

- (mannequin %>% tfd_log_prob(y))

mannequin %>% compile(optimizer = optimizer_adam(lr = learning_rate), loss = negloglik)

hist <-

mannequin %>% match(

X_train[, i, drop = FALSE],

y_train,

validation_data = listing(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE], y_val),

epochs = n_epochs,

batch_size = batch_size

)

yhats <- purrr::map(1:100, operate(x)

mannequin(tf$fixed(X_val[, i, drop = FALSE])))

means <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_mean)) %>% abind::abind()

sds <-

purrr::map(yhats, purrr::compose(as.matrix, tfd_stddev)) %>% abind::abind()

means_gathered <- knowledge.body(cbind(X_val[, i], means)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = mean_val,-X1)

sds_gathered <- knowledge.body(cbind(X_val[, i], sds)) %>%

collect(key = run, worth = sd_val,-X1)

traces <-

means_gathered %>% inner_join(sds_gathered, by = c("X1", "run"))

imply <- apply(means, 1, imply)

#traces <- traces %>% filter(run=="X3" | run =="X4")

ggplot(knowledge.body(x = X_val[, i], y = y_val, imply = as.numeric(imply)), aes(x, y)) +

geom_point() +

theme(legend.place = "none") +

geom_line(aes(x = X_val[, i], y = imply), shade = "violet", measurement = 1.5) +

geom_line(

knowledge = traces,

aes(x = X1, y = mean_val, shade = run),

alpha = 0.2,

measurement = 0.5

) +

geom_ribbon(

knowledge = traces,

aes(

x = X1,

ymin = mean_val - 2 * sd_val,

ymax = mean_val + 2 * sd_val,

group = run

),

alpha = 0.01,

fill = "gray",

inherit.aes = FALSE

)And the output?

Determine 12: Mixed uncertainty on the Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set; single predictors.

This seems to be helpful! Let’s wrap up with our remaining take a look at case: Utilizing all 4 predictors collectively.

All predictors

The coaching code used on this state of affairs seems to be similar to earlier than, aside from our feeding all predictors to the mannequin. For plotting, we resort to displaying the primary principal element on the x-axis – this makes the plots look noisier than earlier than. We additionally show fewer traces for the epistemic and epistemic-plus-aleatoric instances (20 as a substitute of 100). Listed here are the outcomes:

Determine 13: Uncertainty (aleatoric, epistemic, each) on the Mixed Cycle Energy Plant Information Set; all predictors.

Conclusion

The place does this depart us? In comparison with the learnable-dropout strategy described within the prior put up, the best way introduced here’s a lot simpler, quicker, and extra intuitively comprehensible.

The strategies per se are that simple to make use of that on this first introductory put up, we might afford to discover alternate options already: one thing we had no time to do in that earlier exposition.

Actually, we hope this put up leaves you able to do your personal experiments, by yourself knowledge.

Clearly, you’ll have to make selections, however isn’t that the best way it’s in knowledge science? There’s no approach round making selections; we simply needs to be ready to justify them …

Thanks for studying!