How personal are particular person information within the context of machine studying fashions? The information used to coach the mannequin, say. There are

varieties of fashions the place the reply is straightforward. Take k-nearest-neighbors, for instance. There will not be even a mannequin with out the

full dataset. Or assist vector machines. There is no such thing as a mannequin with out the assist vectors. However neural networks? They’re simply

some composition of capabilities, – no information included.

The identical is true for information fed to a deployed deep-learning mannequin. It’s fairly unlikely one may invert the ultimate softmax

output from an enormous ResNet and get again the uncooked enter information.

In idea, then, “hacking” a regular neural internet to spy on enter information sounds illusory. In observe, nevertheless, there may be all the time

some real-world context. The context could also be different datasets, publicly accessible, that may be linked to the “personal” information in

query. This can be a widespread showcase utilized in advocating for differential privateness(Dwork et al. 2006): Take an “anonymized” dataset,

dig up complementary info from public sources, and de-anonymize data advert libitum. Some context in that sense will

typically be utilized in “black-box” assaults, ones that presuppose no insider details about the mannequin to be hacked.

However context may also be structural, akin to within the situation demonstrated on this publish. For instance, assume a distributed

mannequin, the place units of layers run on completely different gadgets – embedded gadgets or cellphones, for instance. (A situation like that

is typically seen as “white-box”(Wu et al. 2016), however in frequent understanding, white-box assaults most likely presuppose some extra

insider information, akin to entry to mannequin structure and even, weights. I’d subsequently favor calling this white-ish at

most.) — Now assume that on this context, it’s potential to intercept, and work together with, a system that executes the deeper

layers of the mannequin. Based mostly on that system’s intermediate-level output, it’s potential to carry out mannequin inversion(Fredrikson et al. 2014),

that’s, to reconstruct the enter information fed into the system.

On this publish, we’ll show such a mannequin inversion assault, mainly porting the strategy given in a

pocket book

discovered within the PySyft repository. We then experiment with completely different ranges of

(epsilon)-privacy, exploring impression on reconstruction success. This second half will make use of TensorFlow Privateness,

launched in a earlier weblog publish.

Half 1: Mannequin inversion in motion

Instance dataset: All of the world’s letters

The general means of mannequin inversion used right here is the next. With no, or scarcely any, insider information a couple of mannequin,

– however given alternatives to repeatedly question it –, I need to discover ways to reconstruct unknown inputs based mostly on simply mannequin

outputs . Independently of unique mannequin coaching, this, too, is a coaching course of; nevertheless, basically it won’t contain

the unique information, as these received’t be publicly accessible. Nonetheless, for greatest success, the attacker mannequin is educated with information as

related as potential to the unique coaching information assumed. Considering of photographs, for instance, and presupposing the favored view

of successive layers representing successively coarse-grained options, we wish that the surrogate information to share as many

illustration areas with the true information as potential – as much as the very highest layers earlier than ultimate classification, ideally.

If we wished to make use of classical MNIST for instance, one factor we may do is to solely use a number of the digits for coaching the

“actual” mannequin; and the remaining, for coaching the adversary. Let’s attempt one thing completely different although, one thing which may make the

enterprise more durable in addition to simpler on the similar time. More durable, as a result of the dataset options exemplars extra complicated than MNIST

digits; simpler due to the identical purpose: Extra may probably be realized, by the adversary, from a fancy job.

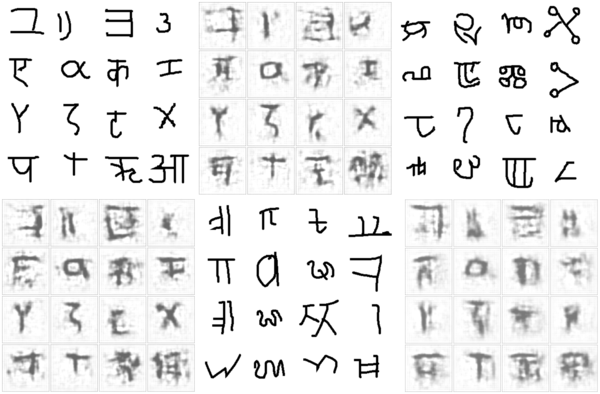

Initially designed to develop a machine mannequin of idea studying and generalization (Lake, Salakhutdinov, and Tenenbaum 2015), the

OmniGlot dataset incorporates characters from fifty alphabets, cut up into two

disjoint teams of thirty and twenty alphabets every. We’ll use the group of twenty to coach our goal mannequin. Here’s a

pattern:

Determine 1: Pattern from the twenty-alphabet set used to coach the goal mannequin (initially: ‘analysis set’)

The group of thirty we don’t use; as a substitute, we’ll make use of two small five-alphabet collections to coach the adversary and to check

reconstruction, respectively. (These small subsets of the unique “massive” thirty-alphabet set are once more disjoint.)

Right here first is a pattern from the set used to coach the adversary.

Determine 2: Pattern from the five-alphabet set used to coach the adversary (initially: ‘background small 1’)

The opposite small subset shall be used to check the adversary’s spying capabilities after coaching. Let’s peek at this one, too:

Determine 3: Pattern from the five-alphabet set used to check the adversary after coaching(initially: ‘background small 2’)

Conveniently, we will use tfds, the R wrapper to TensorFlow Datasets, to load these subsets:

Now first, we practice the goal mannequin.

Practice goal mannequin

The dataset initially has 4 columns: the picture, of measurement 105 x 105; an alphabet id and a within-dataset character id; and a

label. For our use case, we’re not likely within the job the goal mannequin was/is used for; we simply need to get on the

information. Principally, no matter job we select, it isn’t way more than a dummy job. So, let’s simply say we practice the goal to

classify characters by alphabet.

We thus throw out all unneeded options, holding simply the alphabet id and the picture itself:

# normalize and work with a single channel (photographs are black-and-white anyway)

preprocess_image <- perform(picture) {

picture %>%

tf$forged(dtype = tf$float32) %>%

tf$truediv(y = 255) %>%

tf$picture$rgb_to_grayscale()

}

# use the primary 11000 photographs for coaching

train_ds <- omni_train %>%

dataset_take(11000) %>%

dataset_map(perform(document) {

document$picture <- preprocess_image(document$picture)

listing(document$picture, document$alphabet)}) %>%

dataset_shuffle(1000) %>%

dataset_batch(32)

# use the remaining 2180 data for validation

val_ds <- omni_train %>%

dataset_skip(11000) %>%

dataset_map(perform(document) {

document$picture <- preprocess_image(document$picture)

listing(document$picture, document$alphabet)}) %>%

dataset_batch(32)The mannequin consists of two elements. The primary is imagined to run in a distributed style; for instance, on cell gadgets (stage

one). These gadgets then ship mannequin outputs to a central server, the place ultimate outcomes are computed (stage two). Certain, you’ll

be considering, this can be a handy setup for our situation: If we intercept stage one outcomes, we – likely – achieve

entry to richer info than what’s contained in a mannequin’s ultimate output layer. — That’s appropriate, however the situation is

much less contrived than one may assume. Similar to federated studying (McMahan et al. 2016), it fulfills essential desiderata: Precise

coaching information by no means leaves the gadgets, thus staying (in idea!) personal; on the similar time, ingoing site visitors to the server is

considerably decreased.

In our instance setup, the on-device mannequin is a convnet, whereas the server mannequin is an easy feedforward community.

We hyperlink each collectively as a TargetModel that when known as usually, will run each steps in succession. Nonetheless, we’ll have the ability

to name target_model$mobile_step() individually, thereby intercepting intermediate outcomes.

on_device_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(7, 7),

input_shape = c(105, 105, 1), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(3, 3), strides = 3) %>%

layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(7, 7), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(3, 3), strides = 2) %>%

layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(5, 5), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2), strides = 2) %>%

layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(3, 3), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2), strides = 2) %>%

layer_dropout(0.2)

server_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_dense(items = 256, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

# we have now simply 20 completely different ids, however they aren't in lexicographic order

layer_dense(items = 50, activation = "softmax")

target_model <- perform() {

keras_model_custom(identify = "TargetModel", perform(self) {

self$on_device_model <-on_device_model

self$server_model <- server_model

self$mobile_step <- perform(inputs)

self$on_device_model(inputs)

self$server_step <- perform(inputs)

self$server_model(inputs)

perform(inputs, masks = NULL) {

inputs %>%

self$mobile_step() %>%

self$server_step()

}

})

}

mannequin <- target_model()The general mannequin is a Keras customized mannequin, so we practice it TensorFlow 2.x –

type. After ten epochs, coaching and validation accuracy are at ~0.84

and ~0.73, respectively – not unhealthy in any respect for a 20-class discrimination job.

loss <- loss_sparse_categorical_crossentropy

optimizer <- optimizer_adam()

train_loss <- tf$keras$metrics$Imply(identify='train_loss')

train_accuracy <- tf$keras$metrics$SparseCategoricalAccuracy(identify='train_accuracy')

val_loss <- tf$keras$metrics$Imply(identify='val_loss')

val_accuracy <- tf$keras$metrics$SparseCategoricalAccuracy(identify='val_accuracy')

train_step <- perform(photographs, labels) {

with (tf$GradientTape() %as% tape, {

predictions <- mannequin(photographs)

l <- loss(labels, predictions)

})

gradients <- tape$gradient(l, mannequin$trainable_variables)

optimizer$apply_gradients(purrr::transpose(listing(

gradients, mannequin$trainable_variables

)))

train_loss(l)

train_accuracy(labels, predictions)

}

val_step <- perform(photographs, labels) {

predictions <- mannequin(photographs)

l <- loss(labels, predictions)

val_loss(l)

val_accuracy(labels, predictions)

}

training_loop <- tf_function(autograph(perform(train_ds, val_ds) {

for (b1 in train_ds) {

train_step(b1[[1]], b1[[2]])

}

for (b2 in val_ds) {

val_step(b2[[1]], b2[[2]])

}

tf$print("Practice accuracy", train_accuracy$consequence(),

" Validation Accuracy", val_accuracy$consequence())

train_loss$reset_states()

train_accuracy$reset_states()

val_loss$reset_states()

val_accuracy$reset_states()

}))

for (epoch in 1:10) {

cat("Epoch: ", epoch, " -----------n")

training_loop(train_ds, val_ds)

}Epoch: 1 -----------

Practice accuracy 0.195090905 Validation Accuracy 0.376605511

Epoch: 2 -----------

Practice accuracy 0.472272724 Validation Accuracy 0.5243119

...

...

Epoch: 9 -----------

Practice accuracy 0.821454525 Validation Accuracy 0.720183492

Epoch: 10 -----------

Practice accuracy 0.840454519 Validation Accuracy 0.726605475Now, we practice the adversary.

Practice adversary

The adversary’s common technique shall be:

- Feed its small, surrogate dataset to the on-device mannequin. The output obtained might be thought to be a (extremely)

compressed model of the unique photographs. - Pass that “compressed” model as enter to its personal mannequin, which tries to reconstruct the unique photographs from the

sparse code. - Evaluate unique photographs (these from the surrogate dataset) to the reconstruction pixel-wise. The purpose is to attenuate

the imply (squared, say) error.

Doesn’t this sound so much just like the decoding facet of an autoencoder? No marvel the attacker mannequin is a deconvolutional community.

Its enter – equivalently, the on-device mannequin’s output – is of measurement batch_size x 1 x 1 x 32. That’s, the data is

encoded in 32 channels, however the spatial decision is 1. Similar to in an autoencoder working on photographs, we have to

upsample till we arrive on the unique decision of 105 x 105.

That is precisely what’s taking place within the attacker mannequin:

attack_model <- perform() {

keras_model_custom(identify = "AttackModel", perform(self) {

self$conv1 <-layer_conv_2d_transpose(filters = 32, kernel_size = 9,

padding = "legitimate",

strides = 1, activation = "relu")

self$conv2 <- layer_conv_2d_transpose(filters = 32, kernel_size = 7,

padding = "legitimate",

strides = 2, activation = "relu")

self$conv3 <- layer_conv_2d_transpose(filters = 1, kernel_size = 7,

padding = "legitimate",

strides = 2, activation = "relu")

self$conv4 <- layer_conv_2d_transpose(filters = 1, kernel_size = 5,

padding = "legitimate",

strides = 2, activation = "relu")

perform(inputs, masks = NULL) {

inputs %>%

# bs * 9 * 9 * 32

# output = strides * (enter - 1) + kernel_size - 2 * padding

self$conv1() %>%

# bs * 23 * 23 * 32

self$conv2() %>%

# bs * 51 * 51 * 1

self$conv3() %>%

# bs * 105 * 105 * 1

self$conv4()

}

})

}

attacker = attack_model()To coach the adversary, we use one of many small (five-alphabet) subsets. To reiterate what was stated above, there is no such thing as a overlap

with the information used to coach the goal mannequin.

Right here, then, is the attacker coaching loop, striving to refine the decoding course of over 100 – quick – epochs:

attacker_criterion <- loss_mean_squared_error

attacker_optimizer <- optimizer_adam()

attacker_loss <- tf$keras$metrics$Imply(identify='attacker_loss')

attacker_mse <- tf$keras$metrics$MeanSquaredError(identify='attacker_mse')

attacker_step <- perform(photographs) {

attack_input <- mannequin$mobile_step(photographs)

with (tf$GradientTape() %as% tape, {

generated <- attacker(attack_input)

l <- attacker_criterion(photographs, generated)

})

gradients <- tape$gradient(l, attacker$trainable_variables)

attacker_optimizer$apply_gradients(purrr::transpose(listing(

gradients, attacker$trainable_variables

)))

attacker_loss(l)

attacker_mse(photographs, generated)

}

attacker_training_loop <- tf_function(autograph(perform(attacker_ds) {

for (b in attacker_ds) {

attacker_step(b[[1]])

}

tf$print("mse: ", attacker_mse$consequence())

attacker_loss$reset_states()

attacker_mse$reset_states()

}))

for (epoch in 1:100) {

cat("Epoch: ", epoch, " -----------n")

attacker_training_loop(attacker_ds)

}Epoch: 1 -----------

mse: 0.530902684

Epoch: 2 -----------

mse: 0.201351956

...

...

Epoch: 99 -----------

mse: 0.0413453057

Epoch: 100 -----------

mse: 0.0413028933The query now could be, – does it work? Has the attacker actually realized to deduce precise information from (stage one) mannequin output?

Check adversary

To check the adversary, we use the third dataset we downloaded, containing photographs from 5 yet-unseen alphabets. For show,

we choose simply the primary sixteen data – a very arbitrary choice, in fact.

test_ds <- omni_test %>%

dataset_map(perform(document) {

document$picture <- preprocess_image(document$picture)

listing(document$picture, document$alphabet)}) %>%

dataset_take(16) %>%

dataset_batch(16)

batch <- as_iterator(test_ds) %>% iterator_get_next()

photographs <- batch[[1]]

attack_input <- mannequin$mobile_step(photographs)

generated <- attacker(attack_input) %>% as.array()

generated[generated > 1] <- 1

generated <- generated[ , , , 1]

generated %>%

purrr::array_tree(1) %>%

purrr::map(as.raster) %>%

purrr::iwalk(~{plot(.x)})Similar to through the coaching course of, the adversary queries the goal mannequin (stage one), obtains the compressed

illustration, and makes an attempt to reconstruct the unique picture. (In fact, in the true world, the setup can be completely different in

that the attacker would not be capable to merely examine the photographs, as is the case right here. There would thus must be a way

to intercept, and make sense of, community site visitors.)

To permit for simpler comparability (and enhance suspense …!), right here once more are the precise photographs, which we displayed already when

introducing the dataset:

Determine 4: First photographs from the take a look at set, the way in which they actually look.

And right here is the reconstruction:

Determine 5: First photographs from the take a look at set, as reconstructed by the adversary.

In fact, it’s arduous to say how revealing these “guesses” are. There undoubtedly appears to be a connection to character

complexity; general, it looks as if the Greek and Roman letters, that are the least complicated, are additionally those most simply

reconstructed. Nonetheless, in the long run, how a lot privateness is misplaced will very a lot rely upon contextual elements.

At the beginning, do the exemplars within the dataset characterize people or lessons of people? If – as in actuality

– the character X represents a category, it won’t be so grave if we had been in a position to reconstruct “some X” right here: There are various

Xs within the dataset, all fairly related to one another; we’re unlikely to precisely to have reconstructed one particular, particular person

X. If, nevertheless, this was a dataset of particular person folks, with all Xs being pictures of Alex, then in reconstructing an

X we have now successfully reconstructed Alex.

Second, in much less apparent eventualities, evaluating the diploma of privateness breach will seemingly surpass computation of quantitative

metrics, and contain the judgment of area specialists.

Talking of quantitative metrics although – our instance looks as if an ideal use case to experiment with differential

privateness. Differential privateness is measured by (epsilon) (decrease is best), the primary thought being that solutions to queries to a

system ought to rely as little as potential on the presence or absence of a single (any single) datapoint.

So, we are going to repeat the above experiment, utilizing TensorFlow Privateness (TFP) so as to add noise, in addition to clip gradients, throughout

optimization of the goal mannequin. We’ll attempt three completely different situations, leading to three completely different values for (epsilon)s,

and for every situation, examine the photographs reconstructed by the adversary.

Half 2: Differential privateness to the rescue

Sadly, the setup for this a part of the experiment requires a bit of workaround. Making use of the flexibleness afforded

by TensorFlow 2.x, our goal mannequin has been a customized mannequin, becoming a member of two distinct levels (“cell” and “server”) that might be

known as independently.

TFP, nevertheless, does nonetheless not work with TensorFlow 2.x, that means we have now to make use of old-style, non-eager mannequin definitions and

coaching. Fortunately, the workaround shall be straightforward.

First, load (and probably, set up) libraries, taking care to disable TensorFlow V2 conduct.

The coaching set is loaded, preprocessed and batched (almost) as earlier than.

omni_train <- tfds$load("omniglot", cut up = "take a look at")

batch_size <- 32

train_ds <- omni_train %>%

dataset_take(11000) %>%

dataset_map(perform(document) {

document$picture <- preprocess_image(document$picture)

listing(document$picture, document$alphabet)}) %>%

dataset_shuffle(1000) %>%

# want dataset_repeat() when not keen

dataset_repeat() %>%

dataset_batch(batch_size)Practice goal mannequin – with TensorFlow Privateness

To coach the goal, we put the layers from each levels – “cell” and “server” – into one sequential mannequin. Observe how we

take away the dropout. It’s because noise shall be added throughout optimization anyway.

complete_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(7, 7),

input_shape = c(105, 105, 1),

activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(3, 3), strides = 3) %>%

#layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(7, 7), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(3, 3), strides = 2) %>%

#layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(5, 5), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2), strides = 2) %>%

#layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = c(3, 3), activation = "relu") %>%

layer_batch_normalization() %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2), strides = 2, identify = "mobile_output") %>%

#layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_dense(items = 256, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

#layer_dropout(0.2) %>%

layer_dense(items = 50, activation = "softmax")Utilizing TFP primarily means utilizing a TFP optimizer, one which clips gradients in keeping with some outlined magnitude and provides noise of

outlined measurement. noise_multiplier is the parameter we’re going to differ to reach at completely different (epsilon)s:

l2_norm_clip <- 1

# ratio of the usual deviation to the clipping norm

# we run coaching for every of the three values

noise_multiplier <- 0.7

noise_multiplier <- 0.5

noise_multiplier <- 0.3

# similar as batch measurement

num_microbatches <- k_cast(batch_size, "int32")

learning_rate <- 0.005

optimizer <- tfp$DPAdamGaussianOptimizer(

l2_norm_clip = l2_norm_clip,

noise_multiplier = noise_multiplier,

num_microbatches = num_microbatches,

learning_rate = learning_rate

)In coaching the mannequin, the second essential change for TFP we have to make is to have loss and gradients computed on the

particular person stage.

# want so as to add noise to each particular person contribution

loss <- tf$keras$losses$SparseCategoricalCrossentropy(discount = tf$keras$losses$Discount$NONE)

complete_model %>% compile(loss = loss, optimizer = optimizer, metrics = "sparse_categorical_accuracy")

num_epochs <- 20

n_train <- 13180

historical past <- complete_model %>% match(

train_ds,

# want steps_per_epoch when not in keen mode

steps_per_epoch = n_train/batch_size,

epochs = num_epochs)To check three completely different (epsilon)s, we run this thrice, every time with a unique noise_multiplier. Every time we arrive at

a unique ultimate accuracy.

Here’s a synopsis, the place (epsilon) was computed like so:

compute_priv <- tfp$privateness$evaluation$compute_dp_sgd_privacy

compute_priv$compute_dp_sgd_privacy(

# variety of data in coaching set

n_train,

batch_size,

# noise_multiplier

0.7, # or 0.5, or 0.3

# variety of epochs

20,

# delta - shouldn't exceed 1/variety of examples in coaching set

1e-5)| 0.7 | 4.0 | 0.37 |

| 0.5 | 12.5 | 0.45 |

| 0.3 | 84.7 | 0.56 |

Now, because the adversary received’t name the whole mannequin, we have to “minimize off” the second-stage layers. This leaves us with a mannequin

that executes stage-one logic solely. We save its weights, so we will later name it from the adversary:

intercepted <- keras_model(

complete_model$enter,

complete_model$get_layer("mobile_output")$output

)

intercepted %>% save_model_hdf5("./intercepted.hdf5")Practice adversary (in opposition to differentially personal goal)

In coaching the adversary, we will hold a lot of the unique code – that means, we’re again to TF-2 type. Even the definition of

the goal mannequin is identical as earlier than:

on_device_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

[...]

server_model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

[...]

target_model <- perform() {

keras_model_custom(identify = "TargetModel", perform(self) {

self$on_device_model <-on_device_model

self$server_model <- server_model

self$mobile_step <- perform(inputs)

self$on_device_model(inputs)

self$server_step <- perform(inputs)

self$server_model(inputs)

perform(inputs, masks = NULL) {

inputs %>%

self$mobile_step() %>%

self$server_step()

}

})

}

intercepted <- target_model()However now, we load the educated goal’s weights into the freshly outlined mannequin’s “cell stage”:

intercepted$on_device_model$load_weights("intercepted.hdf5")And now, we’re again to the previous coaching routine. Testing setup is identical as earlier than, as properly.

So how properly does the adversary carry out with differential privateness added to the image?

Check adversary (in opposition to differentially personal goal)

Right here, ordered by lowering (epsilon), are the reconstructions. Once more, we chorus from judging the outcomes, for a similar

causes as earlier than: In real-world functions, whether or not privateness is preserved “properly sufficient” will rely upon the context.

Right here, first, are reconstructions from the run the place the least noise was added.

Determine 6: Reconstruction makes an attempt from a setup the place the goal mannequin was educated with an epsilon of 84.7.

On to the subsequent stage of privateness safety:

Determine 7: Reconstruction makes an attempt from a setup the place the goal mannequin was educated with an epsilon of 12.5.

And the highest-(epsilon) one:

Determine 8: Reconstruction makes an attempt from a setup the place the goal mannequin was educated with an epsilon of 4.0.

Conclusion

All through this publish, we’ve kept away from “over-commenting” on outcomes, and targeted on the why-and-how as a substitute. That is

as a result of in a man-made setup, chosen to facilitate exposition of ideas and strategies, there actually is not any goal body of

reference. What is an efficient reconstruction? What is an efficient (epsilon)? What constitutes a knowledge breach? No-one is aware of.

In the true world, there’s a context to the whole lot – there are folks concerned, the folks whose information we’re speaking about.

There are organizations, laws, legal guidelines. There are summary ideas, and there are implementations; completely different

implementations of the identical “thought” can differ.

As in machine studying general, analysis papers on privacy-, ethics- or in any other case society-related matters are filled with LaTeX

formulae. Amid the maths, let’s not overlook the folks.

Thanks for studying!

Fredrikson, Matthew, Eric Lantz, Somesh Jha, Simon Lin, David Web page, and Thomas Ristenpart. 2014. “Privateness in Pharmacogenetics: An Finish-to-Finish Case Examine of Personalised Warfarin Dosing.” In Proceedings of the twenty third USENIX Convention on Safety Symposium, 17–32. SEC’14. USA: USENIX Affiliation.

Wu, X., M. Fredrikson, S. Jha, and J. F. Naughton. 2016. “A Methodology for Formalizing Mannequin-Inversion Assaults.” In 2016 IEEE twenty ninth Pc Safety Foundations Symposium (CSF), 355–70.