It’s 2019; nobody doubts the effectiveness of deep studying in laptop imaginative and prescient. Or pure language processing. With “regular,” Excel-style, a.ok.a. tabular knowledge nevertheless, the state of affairs is totally different.

Mainly there are two circumstances: One, you could have numeric knowledge solely. Then, creating the community is simple, and all will likely be about optimization and hyperparameter search. Two, you could have a mixture of numeric and categorical knowledge, the place categorical might be something from ordered-numeric to symbolic (e.g., textual content). On this latter case, with categorical knowledge coming into the image, there’s a particularly good thought you can also make use of: embed what are equidistant symbols right into a high-dimensional, numeric illustration. In that new illustration, we will outline a distance metric that permits us to make statements like “biking is nearer to working than to baseball,” or “😃 is nearer to 😂 than to 😠.” When not coping with language knowledge, this system is known as entity embeddings.

Good as this sounds, why don’t we see entity embeddings used on a regular basis? Properly, making a Keras community that processes a mixture of numeric and categorical knowledge used to require a little bit of an effort. With TensorFlow’s new characteristic columns, usable from R by way of a mixture of tfdatasets and keras, there’s a a lot simpler option to obtain this. What’s extra, tfdatasets follows the favored recipes idiom to initialize, refine, and apply a characteristic specification %>%-style. And eventually, there are ready-made steps for bucketizing a numeric column, or hashing it, or creating crossed columns to seize interactions.

This put up introduces characteristic specs ranging from a situation the place they don’t exist: principally, the established order till very not too long ago. Think about you could have a dataset like that from the Porto Seguro automobile insurance coverage competitors the place a few of the columns are numeric, and a few are categorical. You need to practice a totally linked community on it, with all categorical columns fed into embedding layers. How are you going to try this? We then distinction this with the characteristic spec method, which makes issues quite a bit simpler – particularly when there’s a variety of categorical columns.

In a second utilized instance, we show using crossed columns on the rugged dataset from Richard McElreath’s rethinking package deal. Right here, we additionally direct consideration to a couple technical particulars which might be price understanding about.

Mixing numeric knowledge and embeddings, the pre-feature-spec method

Our first instance dataset is taken from Kaggle. Two years in the past, Brazilian automobile insurance coverage firm Porto Seguro requested contributors to foretell how possible it’s a automobile proprietor will file a declare based mostly on a mixture of traits collected through the earlier yr. The dataset is relatively massive – there are ~ 600,000 rows within the coaching set, with 57 predictors. Amongst others, options are named in order to point the kind of the info – binary, categorical, or steady/ordinal.

Whereas it’s frequent in competitions to attempt to reverse-engineer column meanings, right here we simply make use of the kind of the info, and see how far that will get us.

Concretely, this implies we need to

- use binary options simply the way in which they’re, as zeroes and ones,

- scale the remaining numeric options to imply 0 and variance 1, and

- embed the explicit variables (each by itself).

We’ll then outline a dense community to foretell goal, the binary consequence. So first, let’s see how we might get our knowledge into form, in addition to construct up the community, in a “handbook,” pre-feature-columns method.

When loading libraries, we already use the variations we’ll want very quickly: Tensorflow 2 (>= beta 1), and the event (= Github) variations of tfdatasets and keras:

On this first model of making ready the info, we make our lives simpler by assigning totally different R varieties, based mostly on what the options symbolize (categorical, binary, or numeric qualities):

# downloaded from https://www.kaggle.com/c/porto-seguro-safe-driver-prediction/knowledge

path <- "practice.csv"

porto <- read_csv(path) %>%

choose(-id) %>%

# to acquire variety of distinctive ranges, later

mutate_at(vars(ends_with("cat")), issue) %>%

# to simply maintain them aside from the non-binary numeric knowledge

mutate_at(vars(ends_with("bin")), as.integer)

porto %>% glimpse()Observations: 595,212

Variables: 58

$ goal <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_01 <dbl> 2, 1, 5, 0, 0, 5, 2, 5, 5, 1, 5, 2, 2, 1, 5, 5,…

$ ps_ind_02_cat <fct> 2, 1, 4, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_ind_03 <dbl> 5, 7, 9, 2, 0, 4, 3, 4, 3, 2, 2, 3, 1, 3, 11, 3…

$ ps_ind_04_cat <fct> 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1,…

$ ps_ind_05_cat <fct> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_06_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_07_bin <int> 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1,…

$ ps_ind_08_bin <int> 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_09_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,…

$ ps_ind_10_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_11_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_12_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_13_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_14 <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_15 <dbl> 11, 3, 12, 8, 9, 6, 8, 13, 6, 4, 3, 9, 10, 12, …

$ ps_ind_16_bin <int> 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_17_bin <int> 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_ind_18_bin <int> 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1,…

$ ps_reg_01 <dbl> 0.7, 0.8, 0.0, 0.9, 0.7, 0.9, 0.6, 0.7, 0.9, 0.…

$ ps_reg_02 <dbl> 0.2, 0.4, 0.0, 0.2, 0.6, 1.8, 0.1, 0.4, 0.7, 1.…

$ ps_reg_03 <dbl> 0.7180703, 0.7660777, -1.0000000, 0.5809475, 0.…

$ ps_car_01_cat <fct> 10, 11, 7, 7, 11, 10, 6, 11, 10, 11, 11, 11, 6,…

$ ps_car_02_cat <fct> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_car_03_cat <fct> -1, -1, -1, 0, -1, -1, -1, 0, -1, 0, -1, -1, -1…

$ ps_car_04_cat <fct> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 9,…

$ ps_car_05_cat <fct> 1, -1, -1, 1, -1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, -1, -1, -1, 1,…

$ ps_car_06_cat <fct> 4, 11, 14, 11, 14, 14, 11, 11, 14, 14, 13, 11, …

$ ps_car_07_cat <fct> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_car_08_cat <fct> 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0,…

$ ps_car_09_cat <fct> 0, 2, 2, 3, 2, 0, 0, 2, 0, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0,…

$ ps_car_10_cat <fct> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_car_11_cat <fct> 12, 19, 60, 104, 82, 104, 99, 30, 68, 104, 20, …

$ ps_car_11 <dbl> 2, 3, 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 1, 2,…

$ ps_car_12 <dbl> 0.4000000, 0.3162278, 0.3162278, 0.3741657, 0.3…

$ ps_car_13 <dbl> 0.8836789, 0.6188165, 0.6415857, 0.5429488, 0.5…

$ ps_car_14 <dbl> 0.3708099, 0.3887158, 0.3472751, 0.2949576, 0.3…

$ ps_car_15 <dbl> 3.605551, 2.449490, 3.316625, 2.000000, 2.00000…

$ ps_calc_01 <dbl> 0.6, 0.3, 0.5, 0.6, 0.4, 0.7, 0.2, 0.1, 0.9, 0.…

$ ps_calc_02 <dbl> 0.5, 0.1, 0.7, 0.9, 0.6, 0.8, 0.6, 0.5, 0.8, 0.…

$ ps_calc_03 <dbl> 0.2, 0.3, 0.1, 0.1, 0.0, 0.4, 0.5, 0.1, 0.6, 0.…

$ ps_calc_04 <dbl> 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 4, 2, 3, 2,…

$ ps_calc_05 <dbl> 1, 1, 2, 4, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_calc_06 <dbl> 10, 9, 9, 7, 6, 8, 8, 7, 7, 8, 8, 8, 8, 10, 8, …

$ ps_calc_07 <dbl> 1, 5, 1, 1, 3, 2, 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 4, 1, 2, 5,…

$ ps_calc_08 <dbl> 10, 8, 8, 8, 10, 11, 8, 6, 9, 9, 9, 10, 11, 8, …

$ ps_calc_09 <dbl> 1, 1, 2, 4, 2, 3, 3, 1, 4, 1, 4, 1, 1, 3, 3, 2,…

$ ps_calc_10 <dbl> 5, 7, 7, 2, 12, 8, 10, 13, 11, 11, 7, 8, 9, 8, …

$ ps_calc_11 <dbl> 9, 3, 4, 2, 3, 4, 3, 7, 4, 3, 6, 9, 6, 2, 4, 5,…

$ ps_calc_12 <dbl> 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 5, 3, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2,…

$ ps_calc_13 <dbl> 5, 1, 7, 4, 1, 0, 0, 3, 1, 0, 3, 1, 3, 4, 3, 6,…

$ ps_calc_14 <dbl> 8, 9, 7, 9, 3, 9, 10, 6, 5, 6, 6, 10, 8, 3, 9, …

$ ps_calc_15_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_calc_16_bin <int> 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1,…

$ ps_calc_17_bin <int> 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1,…

$ ps_calc_18_bin <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

$ ps_calc_19_bin <int> 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1,…

$ ps_calc_20_bin <int> 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0,…We cut up off 25% for validation.

The one factor we need to do to the knowledge earlier than defining the community is scaling the numeric options. Binary and categorical options can keep as is, with the minor correction that for the explicit ones, we’ll really move the community the numeric illustration of the issue knowledge.

Right here is the scaling.

train_means <- colMeans(x_train[sapply(x_train, is.double)]) %>% unname()

train_sds <- apply(x_train[sapply(x_train, is.double)], 2, sd) %>% unname()

train_sds[train_sds == 0] <- 0.000001

x_train[sapply(x_train, is.double)] <- sweep(

x_train[sapply(x_train, is.double)],

2,

train_means

) %>%

sweep(2, train_sds, "/")

x_test[sapply(x_test, is.double)] <- sweep(

x_test[sapply(x_test, is.double)],

2,

train_means

) %>%

sweep(2, train_sds, "/")When constructing the community, we have to specify the enter and output dimensionalities for the embedding layers. Enter dimensionality refers back to the variety of totally different symbols that “are available in”; in NLP duties this might be the vocabulary measurement whereas right here, it’s merely the variety of values a variable can take.

Output dimensionality, the capability of the inner illustration, can then be calculated based mostly on some heuristic. Under, we’ll observe a well-liked rule of thumb that takes the sq. root of the dimensionality of the enter.

In order half one of many community, right here we construct up the embedding layers in a loop, every wired to the enter layer that feeds it:

# variety of ranges per issue, required to specify enter dimensionality for

# the embedding layers

n_levels_in <- map(x_train %>% select_if(is.issue), compose(size, ranges)) %>%

unlist()

# output dimensionality for the embedding layers, want +1 as a result of Python is 0-based

n_levels_out <- n_levels_in %>% sqrt() %>% trunc() %>% `+`(1)

# every embedding layer will get its personal enter layer

cat_inputs <- map(n_levels_in, perform(l) layer_input(form = 1)) %>%

unname()

# assemble the embedding layers, connecting every to its enter

embedding_layers <- vector(mode = "listing", size = size(cat_inputs))

for (i in 1:size(cat_inputs)) {

embedding_layer <- cat_inputs[[i]] %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = n_levels_in[[i]] + 1, output_dim = n_levels_out[[i]]) %>%

layer_flatten()

embedding_layers[[i]] <- embedding_layer

}In case you have been questioning concerning the flatten layer following every embedding: We have to squeeze out the third dimension (launched by the embedding layers) from the tensors, successfully rendering them rank-2.

That’s as a result of we need to mix them with the rank-2 tensor popping out of the dense layer processing the numeric options.

So as to have the ability to mix it with something, we’ve to really assemble that dense layer first. It will likely be linked to a single enter layer, of form 43, that takes within the numeric options we scaled in addition to the binary options we left untouched:

# create a single enter and a dense layer for the numeric knowledge

quant_input <- layer_input(form = 43)

quant_dense <- quant_input %>% layer_dense(items = 64)Are elements assembled, we wire them collectively utilizing layer_concatenate, and we’re good to name keras_model to create the ultimate graph.

intermediate_layers <- listing(embedding_layers, listing(quant_dense)) %>% flatten()

inputs <- listing(cat_inputs, listing(quant_input)) %>% flatten()

l <- 0.25

output <- layer_concatenate(intermediate_layers) %>%

layer_dense(items = 30, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 10, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 5, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 1, activation = "sigmoid", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l))

mannequin <- keras_model(inputs, output)Now, should you’ve really learn by way of the entire of this half, you could want for a better option to get so far. So let’s change to characteristic specs for the remainder of this put up.

Function specs to the rescue

In spirit, the way in which characteristic specs are outlined follows the instance of the recipes package deal. (It received’t make you hungry, although.) You initialize a characteristic spec with the prediction goal – feature_spec(goal ~ .), after which use the %>% to inform it what to do with particular person columns. “What to do” right here signifies two issues:

- First, how one can “learn in” the info. Are they numeric or categorical, and if categorical, what am I alleged to do with them? For instance, ought to I deal with all distinct symbols as distinct, leading to, doubtlessly, an infinite depend of classes – or ought to I constrain myself to a hard and fast variety of entities? Or hash them, even?

- Second, optionally available subsequent transformations. Numeric columns could also be bucketized; categorical columns could also be embedded. Or options might be mixed to seize interplay.

On this put up, we show using a subset of step_ features. The vignettes on Function columns and Function specs illustrate further features and their software.

Ranging from the start once more, right here is the whole code for knowledge read-in and train-test cut up within the characteristic spec model.

Knowledge-prep-wise, recall what our targets are: go away alone if binary; scale if numeric; embed if categorical.

Specifying all of this doesn’t want various strains of code:

Be aware how right here we’re passing within the coaching set, and similar to with recipes, we received’t have to repeat any of the steps for the validation set. Scaling is taken care of by scaler_standard(), an optionally available transformation perform handed in to step_numeric_column.

Categorical columns are supposed to make use of the whole vocabulary and pipe their outputs into embedding layers.

Now, what really occurred once we referred to as match()? So much – for us, as we removed a ton of handbook preparation. For TensorFlow, nothing actually – it simply got here to learn about just a few items within the graph we’ll ask it to assemble.

However wait, – don’t we nonetheless should construct up that graph ourselves, connecting and concatenating layers?

Concretely, above, we needed to:

- create the proper variety of enter layers, of right form; and

- wire them to their matching embedding layers, of right dimensionality.

So right here comes the true magic, and it has two steps.

First, we simply create the enter layers by calling layer_input_from_dataset:

`

And second, we will extract the options from the characteristic spec and have layer_dense_features create the required layers based mostly on that data:

layer_dense_features(ft_spec$dense_features())With out additional ado, we add just a few dense layers, and there’s our mannequin. Magic!

output <- inputs %>%

layer_dense_features(ft_spec$dense_features()) %>%

layer_dense(items = 30, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 10, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 5, activation = "relu", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l)) %>%

layer_dropout(price = 0.25) %>%

layer_dense(items = 1, activation = "sigmoid", kernel_regularizer = regularizer_l2(l))

mannequin <- keras_model(inputs, output)How can we feed this mannequin? Within the non-feature-columns instance, we might have needed to feed every enter individually, passing an inventory of tensors. Now we will simply move it the whole coaching set :

mannequin %>% match(x = coaching, y = coaching$goal)Within the Kaggle competitors, submissions are evaluated utilizing the normalized Gini coefficient, which we will calculate with the assistance of a brand new metric obtainable in Keras, tf$keras$metrics$AUC(). For coaching, we will use an approximation to the AUC as a consequence of Yan et al. (2003) (Yan et al. 2003). Then coaching is as simple as:

auc <- tf$keras$metrics$AUC()

gini <- custom_metric(title = "gini", perform(y_true, y_pred) {

2*auc(y_true, y_pred) - 1

})

# Yan, L., Dodier, R., Mozer, M. C., & Wolniewicz, R. (2003).

# Optimizing Classifier Efficiency through an Approximation to the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney Statistic.

roc_auc_score <- perform(y_true, y_pred) {

pos = tf$boolean_mask(y_pred, tf$forged(y_true, tf$bool))

neg = tf$boolean_mask(y_pred, !tf$forged(y_true, tf$bool))

pos = tf$expand_dims(pos, 0L)

neg = tf$expand_dims(neg, 1L)

# authentic paper suggests efficiency is strong to precise parameter selection

gamma = 0.2

p = 3

distinction = tf$zeros_like(pos * neg) + pos - neg - gamma

masked = tf$boolean_mask(distinction, distinction < 0.0)

tf$reduce_sum(tf$pow(-masked, p))

}

mannequin %>%

compile(

loss = roc_auc_score,

optimizer = optimizer_adam(),

metrics = listing(auc, gini)

)

mannequin %>%

match(

x = coaching,

y = coaching$goal,

epochs = 50,

validation_data = listing(testing, testing$goal),

batch_size = 512

)

predictions <- predict(mannequin, testing)

Metrics::auc(testing$goal, predictions)After 50 epochs, we obtain an AUC of 0.64 on the validation set, or equivalently, a Gini coefficient of 0.27. Not a foul consequence for a easy absolutely linked community!

We’ve seen how utilizing characteristic columns automates away a variety of steps in establishing the community, so we will spend extra time on really tuning it. That is most impressively demonstrated on a dataset like this, with greater than a handful categorical columns. Nevertheless, to clarify a bit extra what to concentrate to when utilizing characteristic columns, it’s higher to decide on a smaller instance the place we will simply do some peeking round.

Let’s transfer on to the second software.

Interactions, and what to look out for

To show using step_crossed_column to seize interactions, we make use of the rugged dataset from Richard McElreath’s rethinking package deal.

We need to predict log GDP based mostly on terrain ruggedness, for a variety of international locations (170, to be exact). Nevertheless, the impact of ruggedness is totally different in Africa versus different continents. Citing from Statistical Rethinking

It is smart that ruggedness is related to poorer international locations, in a lot of the world. Rugged terrain means transport is troublesome. Which implies market entry is hampered. Which implies diminished gross home product. So the reversed relationship inside Africa is puzzling. Why ought to troublesome terrain be related to greater GDP per capita?

If this relationship is in any respect causal, it could be as a result of rugged areas of Africa have been protected in opposition to the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades. Slavers most well-liked to raid simply accessed settlements, with simple routes to the ocean. These areas that suffered beneath the slave commerce understandably proceed to endure economically, lengthy after the decline of slave-trading markets. Nevertheless, an consequence like GDP has many influences, and is moreover a wierd measure of financial exercise. So it’s arduous to make certain what’s happening right here.

Whereas the causal state of affairs is troublesome, the purely technical one is definitely described: We need to be taught an interplay. We might depend on the community discovering out by itself (on this case it most likely will, if we simply give it sufficient parameters). Nevertheless it’s a superb event to showcase the brand new step_crossed_column.

Loading the dataset, zooming in on the variables of curiosity, and normalizing them the way in which it’s finished in Rethinking, we’ve:

Observations: 170

Variables: 3

$ log_gdp <dbl> 0.8797119, 0.9647547, 1.1662705, 1.1044854, 0.9149038,…

$ rugged <dbl> 0.1383424702, 0.5525636891, 0.1239922606, 0.1249596904…

$ africa <int> 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …Now, let’s first overlook concerning the interplay and do the very minimal factor required to work with this knowledge.

rugged needs to be a numeric column, whereas africa is categorical in nature, which suggests we use one of many step_categorical_[...] features on it. (On this case we occur to know there are simply two classes, Africa and not-Africa, so we might as effectively deal with the column as numeric like within the earlier instance; however in different functions that received’t be the case, so right here we present a way that generalizes to categorical options normally.)

So we begin out making a characteristic spec and including the 2 predictor columns. We test the consequence utilizing feature_spec’s dense_features() technique:

$rugged

NumericColumn(key='rugged', form=(1,), default_value=None, dtype=tf.float32, normalizer_fn=None)Hm, that doesn’t look too good. The place’d africa go? In actual fact, there’s yet one more factor we should always have finished: convert the explicit column to an indicator column. Why?

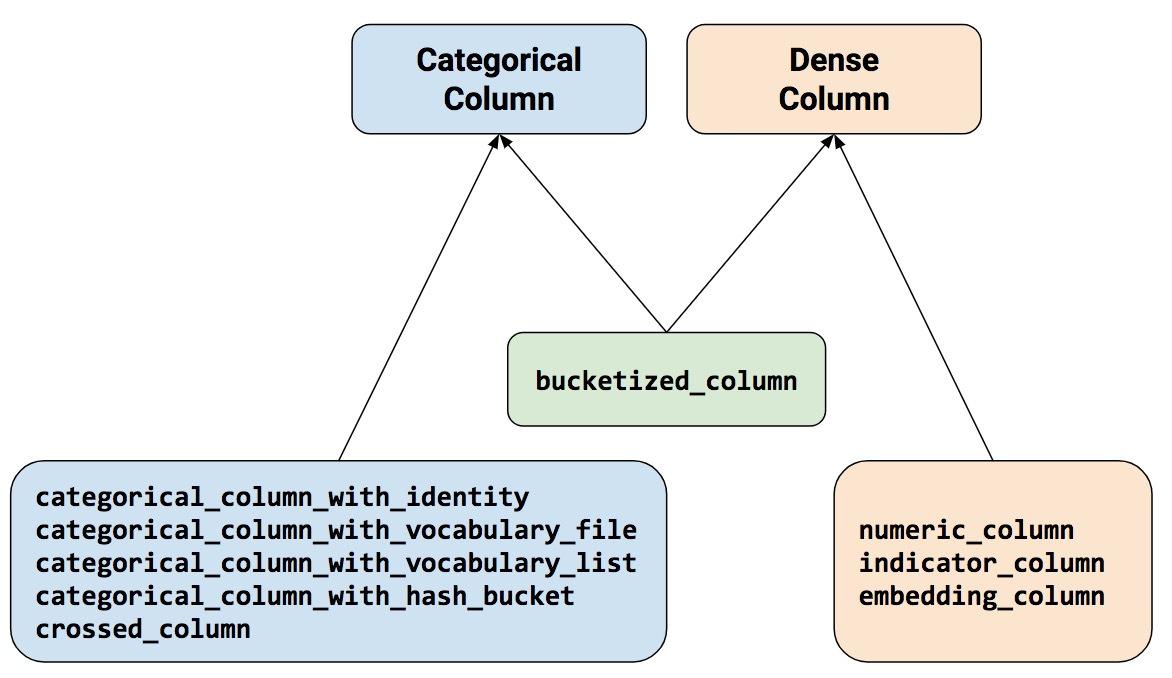

The rule of thumb is, at any time when you could have one thing categorical, together with crossed, it is advisable to then remodel it into one thing numeric, which incorporates indicator and embedding.

Being a heuristic, this rule works total, and it matches our instinct. There’s one exception although, step_bucketized_column, which though it “feels” categorical really doesn’t want that conversion.

Subsequently, it’s best to complement that instinct with a easy lookup diagram, which can also be a part of the characteristic columns vignette.

With this diagram, the straightforward rule is: We all the time want to finish up with one thing that inherits from DenseColumn. So:

step_numeric_column,step_indicator_column, andstep_embedding_columnare standalone;step_bucketized_columnis, too, nevertheless categorical it “feels”; and- all

step_categorical_column_[...], in addition tostep_crossed_column, should be reworked utilizing one the dense column varieties.

Determine 1: To be used with Keras, all options want to finish up inheriting from DenseColumn one way or the other.

Thus, we will repair the state of affairs like so:

and now ft_spec$dense_features() will present us

$rugged

NumericColumn(key='rugged', form=(1,), default_value=None, dtype=tf.float32, normalizer_fn=None)

$indicator_africa

IndicatorColumn(categorical_column=IdentityCategoricalColumn(key='africa', number_buckets=2.0, default_value=None))

What we actually wished to do is seize the interplay between ruggedness and continent. To this finish, we first bucketize rugged, after which cross it with – already binary – africa. As per the principles, we lastly remodel into an indicator column:

ft_spec <- coaching %>%

feature_spec(log_gdp ~ .) %>%

step_numeric_column(rugged) %>%

step_categorical_column_with_identity(africa, num_buckets = 2) %>%

step_indicator_column(africa) %>%

step_bucketized_column(rugged,

boundaries = c(0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8)) %>%

step_crossed_column(africa_rugged_interact = c(africa, bucketized_rugged),

hash_bucket_size = 16) %>%

step_indicator_column(africa_rugged_interact) %>%

match()Taking a look at this code you could be asking your self, now what number of options do I’ve within the mannequin?

Let’s test.

$rugged

NumericColumn(key='rugged', form=(1,), default_value=None, dtype=tf.float32, normalizer_fn=None)

$indicator_africa

IndicatorColumn(categorical_column=IdentityCategoricalColumn(key='africa', number_buckets=2.0, default_value=None))

$bucketized_rugged

BucketizedColumn(source_column=NumericColumn(key='rugged', form=(1,), default_value=None, dtype=tf.float32, normalizer_fn=None), boundaries=(0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8))

$indicator_africa_rugged_interact

IndicatorColumn(categorical_column=CrossedColumn(keys=(IdentityCategoricalColumn(key='africa', number_buckets=2.0, default_value=None), BucketizedColumn(source_column=NumericColumn(key='rugged', form=(1,), default_value=None, dtype=tf.float32, normalizer_fn=None), boundaries=(0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.8))), hash_bucket_size=16.0, hash_key=None))We see that each one options, authentic or reworked, are saved, so long as they inherit from DenseColumn.

Because of this, for instance, the non-bucketized, steady values of rugged are used as effectively.

Now establishing the coaching goes as anticipated.

inputs <- layer_input_from_dataset(df %>% choose(-log_gdp))

output <- inputs %>%

layer_dense_features(ft_spec$dense_features()) %>%

layer_dense(items = 8, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(items = 8, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(items = 1)

mannequin <- keras_model(inputs, output)

mannequin %>% compile(loss = "mse", optimizer = "adam", metrics = "mse")

historical past <- mannequin %>% match(

x = coaching,

y = coaching$log_gdp,

validation_data = listing(testing, testing$log_gdp),

epochs = 100)Simply as a sanity test, the ultimate loss on the validation set for this code was ~ 0.014. However actually this instance did serve totally different functions.

In a nutshell

Function specs are a handy, elegant method of constructing categorical knowledge obtainable to Keras, in addition to to chain helpful transformations like bucketizing and creating crossed columns. The time you save knowledge wrangling might go into tuning and experimentation. Take pleasure in, and thanks for studying!

Yan, Lian, Robert H Dodier, Michael Mozer, and Richard H Wolniewicz. 2003. “Optimizing Classifier Efficiency through an Approximation to the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney Statistic.” In Proceedings of the twentieth Worldwide Convention on Machine Studying (ICML-03), 848–55.